Lyle Rexler.February, 2010.

Anyone looking for a definition of outside art will find a visit to the Outsider Art Fair, now in its 18th year, confusing, to say the least. Alongside such classic outsider dealers as London’s Henry Boxer, Chicago’s Carl Hammer, and New York’s Phyllis Kind are some specializing in fold art–work arising from a shared repertoire of stories, symbols, and techniques, made for an audience who would likely “get it”–and others devoted almost exclusively to Haitian art, whose painting traditions are anything but naïve. Then there are dealers like Maxwell Projects and Ricco/Maresca Gallery, whose wares seem more contemporary than outsider.

What’s going on here? Its hard to resist the cynical notion that dealers are simply using the fair as still another venue for channeling some of the money flooding the market over the past two decades into their wallets. More and more collectors looking for new artists cruise the event each year as if it were Pulse or Scope. In fact, outsider art is keeping different, more-contemporary company than it used to, and that is slowly but surely rendering the phrase all but meaningless. Jut as important, it is changing the canon of art history.

The term outsider art was coined almost 40 years ago by art historian Roger Cardinal, inspired by Jean Dubuffet’s art brut, or raw art. It designated truly marginal creations, cut off from society’s norms and audiences, produced by people considered insane and usually institutionalized.

Work of this type has been documented at least since the 1300s in the West, and by the time Cardinal came alone, it had long been avidly collected and had influenced modern artists from Paul Klee to Dubuffet himself. The works of outsiders presented unfamiliar visual forms, sexually explicit subjects and jarring juxtapositions of language and text, executed using materials as common as cloth strips and spit and tools as crude as spoons. The visions, often having nothing to do with conventional ideas of beauty, seemed private and isolated from art history and society–hence naïve, primitive, raw, but also pure. Dubuffet’s collection formed the core of the Musée de l’art brut, in Lausanne, Switzerland. In Europe critics maintained rigid and highly political criteria for what qualified as authentic. And they used raw art of the insane as a stick with which to beat the products of bourgeois society–“asphyxiating culture,” Dubuffet called it–and its artists. Many people still consider the term a battle cry.

But in fact, outsiders and insiders have been rubbing shoulders for decades–in modern art galleries. In 1939 the modernist dealer Sidney Janis mounted a show of autodidact artists at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and two years later published They Taught Themselves, the first survey of this category. Few of his examples could be called true outsider works, but they were not mainstream modern art (which was itself aligned against conventional standards of beauty and form). Galerie St. Etienne, which specializes in German expressionism, has represented Grandma Moses since 1940 and was also, in 1993, the first to represent the estate of outsider Henry Darger, the solitary Chicago artist who composed and illustrated a vast and apocalyptic narrative of juvenile violation and war. Since 2001 the venerable Knoedler & Company has mounted shows of work by the quintessential outsider, James Castle, the deaf artist who lived his entire life in rural Idaho.

The Ricco/Maresca Gallery exemplifies the impulse to bring the outsiders in. Founded in 1979 largely as a dealer in folk and vernacular art, the gallery naturally gravitated to work by self-taught talents Bill Traylor, William Edmondson, William Hawkins, Thornton Dial, and the Mexican Martin Ramirez, who produced a torrent of elaborately patterned work during his confinement in California mental hospital. Roger Ricco, a painter, and Frank Maresca, a commercial photographer, had a broader agenda, however “When the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s exhibition ‘Black Folk Art’ [1982] showed the iconic drawings of Traylor, an illiterate former slave who made art for only a brief new years in the 1940s,” says Maresca, “it was clear to a lot of us that, formally speaking, this work would take its place within a spectrum that included modernist art, not outside it.” Since its move to Chelsea in 1997, the gallery has alternated displays of outsiders with those of white-cube contemporary artists, exhibiting, for instance, photographer Joel=Peter Witkin and Hester Simpson, a painter of geometric abstractions. When a cache of drawings by Ramirez came to light two years ago, the owners chose Ricco/Maresca to represent them precisely because of its connection to contemporary art, says Maresca. “We were in competition with other like galleries, and we won the representation. I really don’t think that there was any other gallery in the world that was as conscious about crossover. Our mission was really to introduce this material not to the usual suspects but to the modern and contemporary mainstream.”

The other force drawing outsiders inside has been institutional. In prisons, asylums, hospitals, and community centers, programs based on the belief that art is therapeutic, especially for the mentally ill, have generated work for decades, including, the 1950s, that of Ramirez. Although they have produced important artists, most of these programs have as their main goal socialization and rehabilitation, not aesthetic development. There have been some spectacular exceptions, however, and these have changed the context of outsider art.

By far the best known is the Art/Brut Center Gugging, located outside Vienna. Its Haus der Künstler (artists’ house), founded by the visionary psychiatrist Dr. Leo Navratil in 1981, represents a radical break with the stubborn Viennese tradition of treating the art of the mentally ill as a diagnostic or symptomatic. Navatril insisted that the creations of his patients be considered formal artistic expressions and they benefited from the artists’ living near one another. The artistic output, in quantity and quality, rivals that of any modern art institutions, including the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Patients August Walla, Oswald Tschirtner, Johann Fischer, Johann Hauser, Rudulf Horacek, and Heinrich Reisenbauer provided indelible images for contemporary art and influenced a host of mainstream artists, including Herman Nitsch, Arnulf Rainer, and Georg Baselitz. The Haus der Künstler succeeded so well, in fact, that it is now independent of the clinic and markets the patients’ work itself.

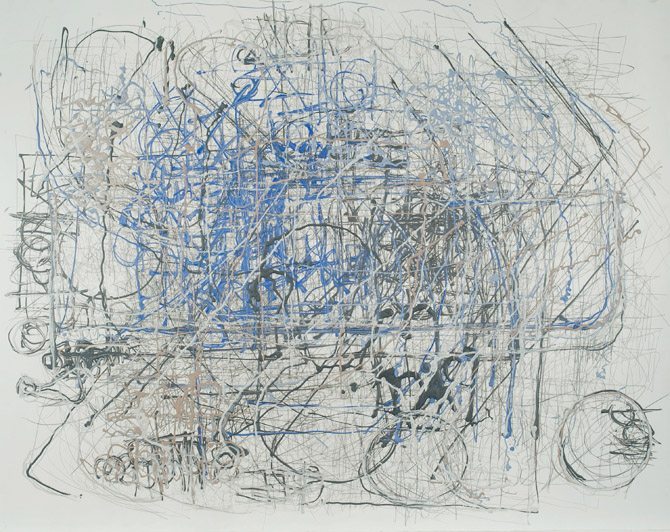

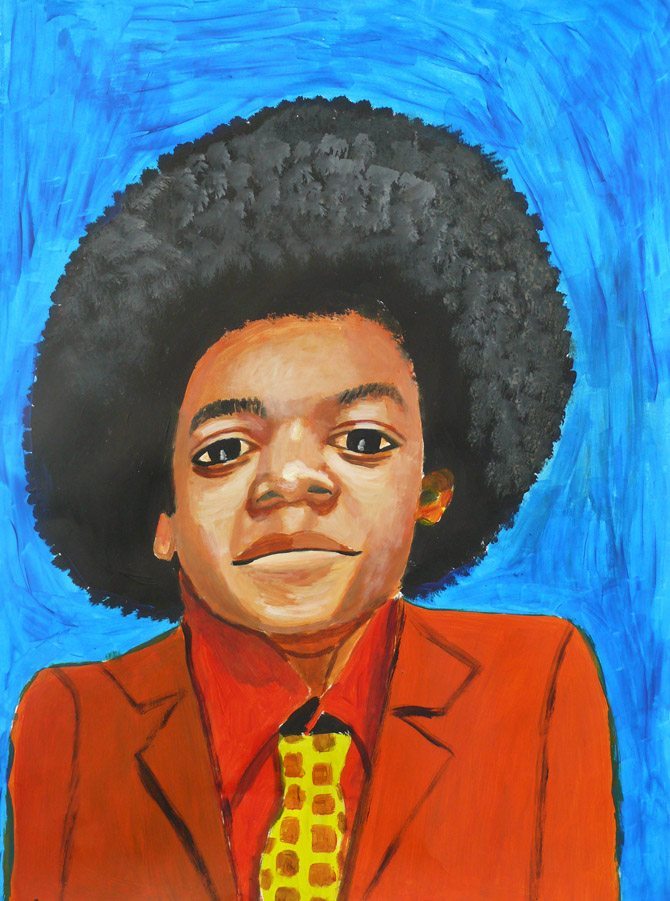

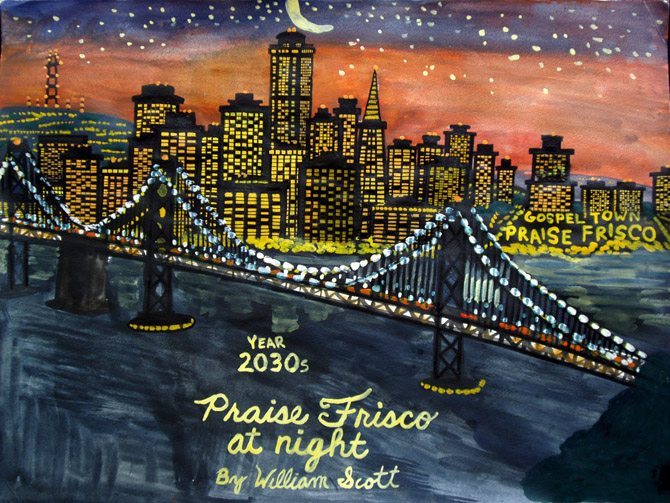

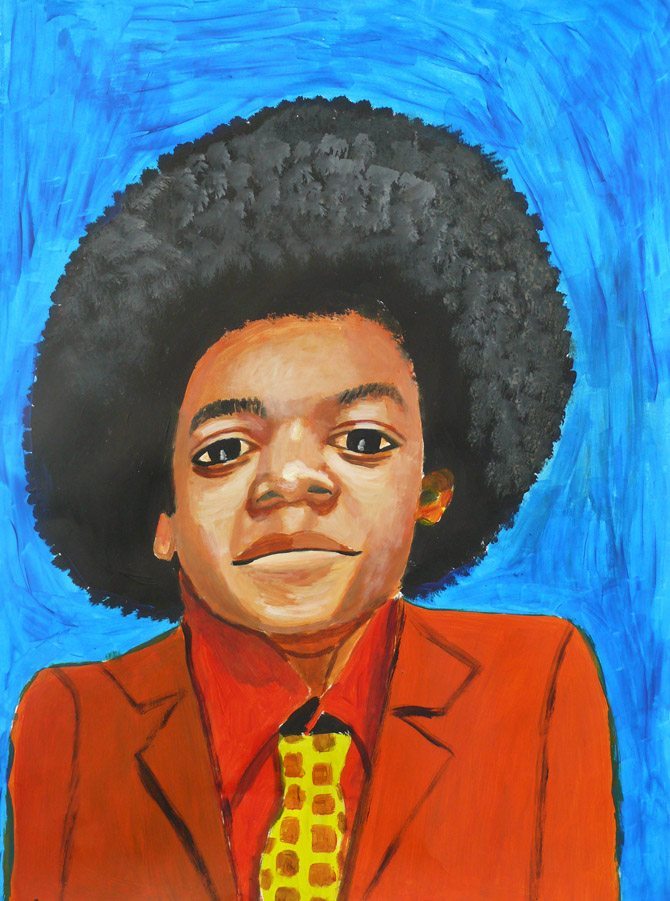

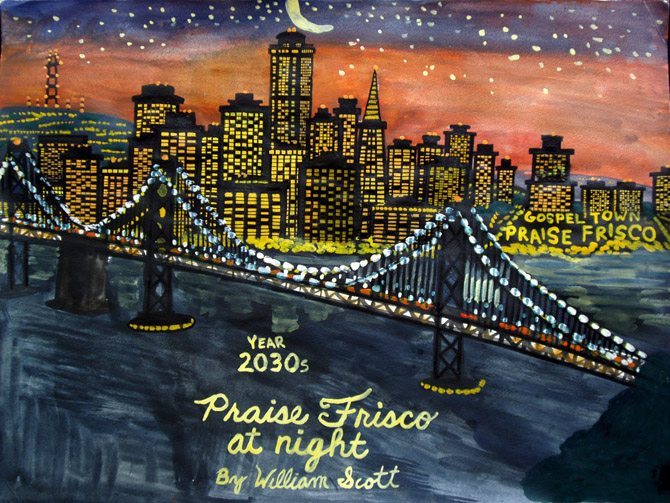

The closest U.S. equivalent in importance is probably Creative Growth Art Center, in Oakland, California. Founded35 years ago to provide arts access to people with disabilities, it was the first program of its kind in the United Sates, and unlike many others, its goal was always aesthetic––to encourage work of high quality, and not just in terms of outsider art. “My ideal,” says director Tom di Maria, “has always been to make this art part of the discussion of contemporary art. My hope is that it will lead contemporary artists.” To that end, Creative Growth has nurtured and aggressively promoted some remarkable talents, including the late Judith Scott, whose wrapped bundles have primal power; Dan Miler, whose idiosyncratic, obsessive drawings and paintings of layered text have been acquired by MOMA; and William Scott, whose idealized urban utopias have earned him shoes at White Columns, and Gavin Brown Enterprise. The center has formed a relationship with the new Paris venue Galerie Impaire, and its artists figure prominently in the Museum of Everything, a vast outsider collection on display at last fall’s Frieze Art Fair, in London.

With artists, collectors, dealers, and grassroots organizations promoting the integration of outsiders, some major U.S. museums have joined the movement. New York’s Drawing Center, the New Museum, and the American Folk Art Museum have made serious efforts to combine outsiders with insiders, and MOMA, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and LACMA have done so intermittently but often significantly, as witness the vast James Castle exhibition in Philadelphia last year.

Because of this exposure, traditional art historians and contemporary critics are paying more attention to outsiders, and in the process debunking some myths about them. All these artists at one time assumed to be hermetic, addressing only themselves in private languages, on closer inspection are seen to have intentions and strategies similar to those of familiar insider artists. It has been demonstrated, for instance, that both Ramirez and Darger, in their different ways, produced relatively coherent symbolic systems that enabled them to address memory, desire, religious conflicts, and personal cultural history. However extreme, their images are not only accessible but meaningful to wide audiences. More dramatically, Bill Traylor’s persona has an affable teller of rural southern folk tales is being overhauled by scholars who detect in his work coded expressions of anger and protest against racial injustice and personal trauma. In her recent book Painting as Hidden Life: The Art of Bill Traylor, Mechal Sobel argues that a hunting scene actually represents the murder of the artist’s son by white police officers.

Conversely, many insider works are now seen to resemble those of outsiders. The creations of Alfred Jensen, Yayoi Kusama, and the contemporary English artist Matthew Ritchie––all insiders––reveal not so much outsider influence as common psychic currents. Unassimilable impulses inform Richie’s extravagant notion of flow and Jensen’s Aztec numerology and color symbolism. As for Kalama, her bouts of mental illness are well known, but her dot-based paintings and installations reveal an obsessive aspect of Minimalism that has gone largely unexplored by critics.

Outsiders don’t consciously participate in the art world, and their presence there will always be to a large degree subject to the will of insiders––the dealers, critics, collectors, and other artists who do the selecting. But there work, through its shared dimensions with contemporary art, throws new light on the latter’s often fragmentary, obsessive, and self-sanctioning character. Call it pluralism or the death of art history as we know it, they are all outsiders now.

Photo by Cheryl Dunn

Photo by Cheryl Dunn