William Scott Featured | Cambridge University Press | Contemporary Outsider Art | April 2016

William Scott: Painting Utopia T. di Maria Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland, California, USA Received 30 January 2016; Accepted 17 March 2016; First published online 18 April 2016 Key words: Autism, contemporary art, outsider art, Schizophrenia.

An artist’s biography, and the personal circumstances under which an artwork is made, can add to our understanding of his or her work. Biography should not be our first concern as we view an artwork, but can play an important role in our full understanding of an artist’s work.

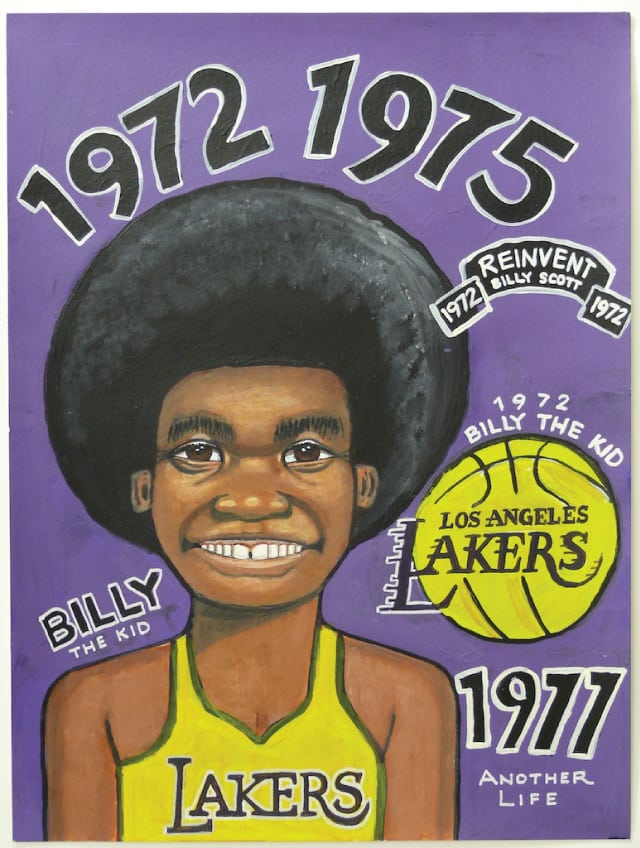

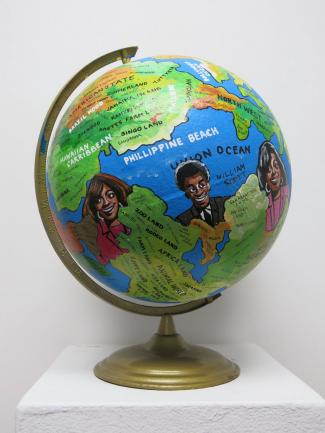

There are infinite possibilities to what a painting can look like. In the paintings of William Scott (b. 1964), we see self-portraits, cityscapes, buildings and pictures of imaginary friends. Aesthetically, these works have compelling associations with photorealistic paintings, West African signage, and architectural studies. Yet the content of these works depict an altered realitythat at first may not be immediately understood. Together, these images depict a utopian world filled with renewed urban structures, revised personal histories and the rebirth of entire cities and their citizens.

There is evidence of artists with autism having the capacity to study and store visual detail and to call forth these memorised elements in their work (Cardinal, 2009). William Scott is such an artist. His architectural depictions of skyscrapers, hospitals and urban landscapes are drafted from memory, often with acute attention to detail and mapping (Figs 1 and 2).

William’s vision of the future, and his talent as an artist, are influenced by his dual diagnosis. Living on the autistic spectrum, and with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, William has developed a style of work that incorporates both his outstanding attention to detail, and his belief in a fantasied utopian reality.

As a child with disabilities growing up in an often violent and economically poor neighbourhood in San Francisco, William was exposed to random street violence, scenes of poverty and neglected urban housing projects. Seeking to rise above these circumstances, he assigned himself a herculean task: to paint away these injustices, and to craft a new order of wholesome positive people living in a renewed and positive world.

With the support of a local librarian, Scott made his way to the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, a noted centre for artists with disabilities. Working there for over 25 years, his painting technique and his path towards fantasy increased. ‘The distance between what Scott believes and imagines and what the audience responds to are different, reflecting the difference between the painting being a kind of time machine to alter reality and a mere depiction of an imaginary new work’ (Trainor, 2006).

As an example, in a self-portrait, Scott depicts himself in 1977 as ‘Billy the Kid.’ Using the painting as a vehicle to travel back to his childhood, he imagines his young self as happy, successful at basketball, popular and without disabilities. The painting becomes a transformative tool, one that reinvents the past with the hope that it will turn his current reality into the life he fully desires.

His memory painting of San Francisco General Hospital is not merely a startling image constructed from recollection, but also a time machine designed to transport Scott back to the moments before an accident sent him to the hospital’s burn unit. Preoccupied by the permanent scar left on his body from the incident, he attempts to paint away the accident itself by going back in time and erasing it from his personal history.

Most striking are Scott’s space ships that fly under the banner of ‘Inner Limits.’ The glowing faces of young African-American men and women who seem to have just stepped from the craft surround these vessels. What we are witnessing is their rebirth. These are people that William cares for, those killed by drugs and street violence. His spaceship is the vehicle for bringing those taken from this world back to us for a second life filled with hope and a new reality.

In the exhibition called Alternative Guide to the Universe, at the Hayward Gallery in London, Ralph Rugoff presented artists whose work seeks to change reality. Scott was in good company with others whose numbering systems, scientific investigations and fantasied realties teetered on the edge of invented new worlds. There, Scott’s work ‘invites us to think outside of our conventional categories and ultimately to question our definitions of ‘normal’ art and science’ (Rugoff, 2013).

One must ask if Scott’s paintings fulfil the hope of the artist, if they do in fact change the reality in which he lives. Scott often struggles with reality not changing in accordance with his paintings. Sparkling new housing projects have not been built; those tragically killed from random violence have not come back to life. However, his art has indeed changed his life. From his early years as a child with disabilities in an under-privileged environment, to an adult whose work has now been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Studio Museum of Harlem, one can argue that his method of transforming reality into a more vibrant and wholesome encounter with the world seems to be working.

References Cardinal R (2009). Outsider Art and the Autistic Creator, Vol. 364, pp. 1459–1466. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B: London. Rugoff R (2013). Alternative Guide to the Universe. Hayward Gallery Publishing: London. Trainor J (2006). Experimental Art, pp. 33–34. Frieze Magazine, London.

About the author Tom di Maria is Director of the Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland, California since 2000. Creative Growth was founded in the early 1970s and is the world’s oldest and largest art center for people with disabilities in the USA. Today the centre serves over 150 artists with developmental disabilities every week in its spacious art studio and gallery. Under di Maria’s administration Creative Growth gained a high-visibility position in the Contemporary Art scene and an impressive market success. Art pieces from Creative Growth are displayed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; at the Oakland Museum of California; at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and were recently acquired by Facebook, Christie’s and the Smithsonian. Prior to pushing the boundaries from Outsider Art into Contemporary Art, di Maria was Assistant Director of the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive at UC Berkeley and Executive Director of GLAAD/ San Francisco, and Director the San Francisco International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival. He recently released the new publication The Creative Growth Book (5 Continents Press) and speaks around the world on Creative Growth’s artists and programmes.

Dan Miller featured in Raw Vision Magazine 88 | By Tom di Maria

Our Artists -- Our Programs and the New York Times

A new article in the New York Times Magazine provides a comprehensive overview of Creative Growth’s history and the compelling work of our artists.

Your support makes this work possible.

Your gifts matter. Please support our 160 artists with disabilities so that Creative Growth can continue to serve them in the years to come.

Donate

Read the Article

John Hiltunen featured in Cindy Sherman's collection

- August 14, 2015 10:00 AM | by W magazine

Cindy Sherman’s eclectic collection includes works by John Hiltunen (upper left), Esther Pearl Watson, James Welling, Dana Schutz, Michele Abeles, Megan Whitmarsh, Martin Kippenberger, Mike Kelley, Chris Garofalo, and Ken Tisa.

Judith Scott featured in New York Times review of 'A Rare Earth Magnet' at Derek Eller Gallery

THE NEW YORK TIMES | ART & DESIGNBy ROBERTA SMITH | AUG. 13, 2015

Review: In ‘A Rare Earth Magnet’ at Derek Eller, a Focus on Repurposed Materials

Derek Eller Gallery

615 West 27th Street, Chelsea

This is one of those late-summer group shows that can stir optimism about the coming season. And it may be germane that eight of the 11 artists here are women. Organized by Brian Faucette, director of the Derek Eller Gallery and co-owner of his own establishment, the Brooklyn gallery Know More Games, the exhibition concentrates on artists avidly drawn to found materials, recycled objects and strong color, with robust, often tactile results. In a reasonable description of contemporary art, the show’s news release states that widespread digitization and “the canonization of poststudio practices” are creating “a materialist counterculture.”

Helpless in the face of Google’s sundry definitions of the term “rare earth magnet,” I can only take the show’s title poetically, as possibly suggesting the counterculture’s irrevocable attraction to physical stuff. The presiding angel here is the fiber artist Judith Scott (1943-2005), represented by one of her wrapped-yarn sculptures — a soft, irregular mass made from a line — that includes vacuum-cleaner tubing among its multicolored strands. And the influential artist Mike Kelley seems present in spirit, especially in Anna Rosen’s insanely cheerful paintings — flowers and a bright sun — appended with lovingly worn knickknacks that evoke a simpler past.

There’s little here that hasn’t had a previous life, whether it’s the slice of bright International Klein Blue bread atop Michelle Segre’s Calderesque sculpture; the baroque arrangements of jump ropes, resin, foam and plastic bread with which Adam Parker Smith playfully conjures the ghosts of Frank Stellas past; or Nancy Shaver’s combining of real and trompe l’oeil painted wood into serene Morandi-like reliefs. Ann Greene Kelly complicates weirdly recycled objects with bits of carved alabaster. Sydney Shen reminds us that hornets’ nests are domestic no-trespass realms. Ajay Kurian builds a kinetic sculpture to torture — or at least change the expressive eyes of — a plastic Minion toy. Both Thomas Barrow and Amy Brener make familiar things strange, as does Anna-Sophie Berger, who contributes two pairs of small sterling silver earrings set with pea seeds.

“Untitled” (2004), a wrapped-yarn sculpture by the fiber artist Judith Scott. Credit Derek Eller Gallery

PRESS RELEASE -- 2015 Beyond Trend Runway Event and Live Auction

EXHIBITION ANNOUNCEMENT Media Contact: Jennifer O’Neal jennifer@www.creativegrowth.org 510-836-2340 x 20

March 23, 2015 — Oakland’s Creative Growth Art Center announces 2015 Beyond Trend Runway Event and Live Auction.

Creative Growth, the world's oldest and largest center for artists with disabilities, presents its much anticipated and wildly inventive annual fundraiser, the Beyond Trend Runway Event and Live Auction--taking place in Oakland on Saturday, April 18, 6-9pm. Tickets are available starting at $125.

Within its 41 year history, Creative Growth has partnered with the world’s leading designers, contemporary artists and galleries. Drawings, paintings and sculpture from the organization’s artist roster are included in the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art along with hundreds of notable collections worldwide.

The Beyond Trend Runway Event and Live Auction, provides critical support in funding the future of Creative Growth's visionary artist community, while offering an unforgettable experience at the intersection of art, fashion, music and highly regarded Bay Area cuisine.

Collaborators include celebrated chefs Cal Peternell of Chez Panisse and Charlie Hallowell of Pizzaiolo; Oakland fashion retailers and runway stylists Karen Anderson and Rachel Cubra of Mercy Vintage and Anne Hartford of Maribel--along with a stellar lineup of over twenty Creative Growth artists, modeling their own hand-made designs during a live runway show. Live music by Los Angeles based, minimal electronic duo, BOUQUET and sets by Djinti.

Auction items available on the night of the event include a private dinner for two in the Chez Panisse kitchen, A VIP filled weekend in New York City during the Outsider Art Fair, and more! Stay tuned to www.creativegrowth.org for auction updates and detailed event information.

Following the event, on Saturday, April 25, from 10am to 3pm the Creative Growth gallery will feature the Beyond Trend Dressing Room--visitors will get an up close look at the designs from the runway and an opportunity to try on over 40 looks from the show, which will also be available for purchase.

Event Details: Saturday, April 18 6-9PM More information about ticket sales at www.creativegrowth.org.

355 24th Street Oakland, CA 94612 (510) 836-2340 x15 www.creativegrowth.org

Creative Growth Featured in the New York Times

Art + Design | Art Review

On the Margins, but Moving Toward the Center Outsider Art Fair Evolves, but Holds Fast to Its Roots

By Martha Schwendener January 29, 2015

Left, “Fleeing Darfur” (2006) by Mary Whitfield of Birmingham, Ala. Right, “Untitled” (1963) by Minnie Evans of North Carolina. CreditLeft, Galerie Bonheur; right, Luise Ross Gallery, New York

Left, “Fleeing Darfur” (2006) by Mary Whitfield of Birmingham, Ala. Right, “Untitled” (1963) by Minnie Evans of North Carolina. CreditLeft, Galerie Bonheur; right, Luise Ross Gallery, New York

Outsider art has changed significantly over the last decade. Where it used to come with a story and a diagnosis (the work was found in an attic or a Dumpster and made by a person with schizophrenia), it has now been included in the 2013 Venice Biennale, Rosemarie Trockel’s 2012 retrospective at the New Museum and acquired by the Museum of Modern Art. Quibbles over whether it should be called outsider, folk or self-taught are less prominent, and there has been somewhat of a shift to supporting living artists.

For instance, the current Outsider Art Fair includes five art therapy centers among its 50 exhibitors. The best-known, Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, Calif., is showing a sculpture by Judith Scott (who died in 2005, and made work at the Center). Her cocoonlike pieces are on view at theBrooklyn Museum, too. The fair is also showing several skeinlike drawings by Dan Miller, whose art was acquired by MoMA. Both use an abstract idiom, demonstrating how so-called outsider trends often echo “insider” ones.

"Untitled (Bird)” (1982) by T. A. Hay, a farmer from Kentucky. Made of shoe polish and marker on a plastic foam tray, it is at Tanner-Hill. Credit Tanner Hill Gallery

"Untitled (Bird)” (1982) by T. A. Hay, a farmer from Kentucky. Made of shoe polish and marker on a plastic foam tray, it is at Tanner-Hill. Credit Tanner Hill Gallery

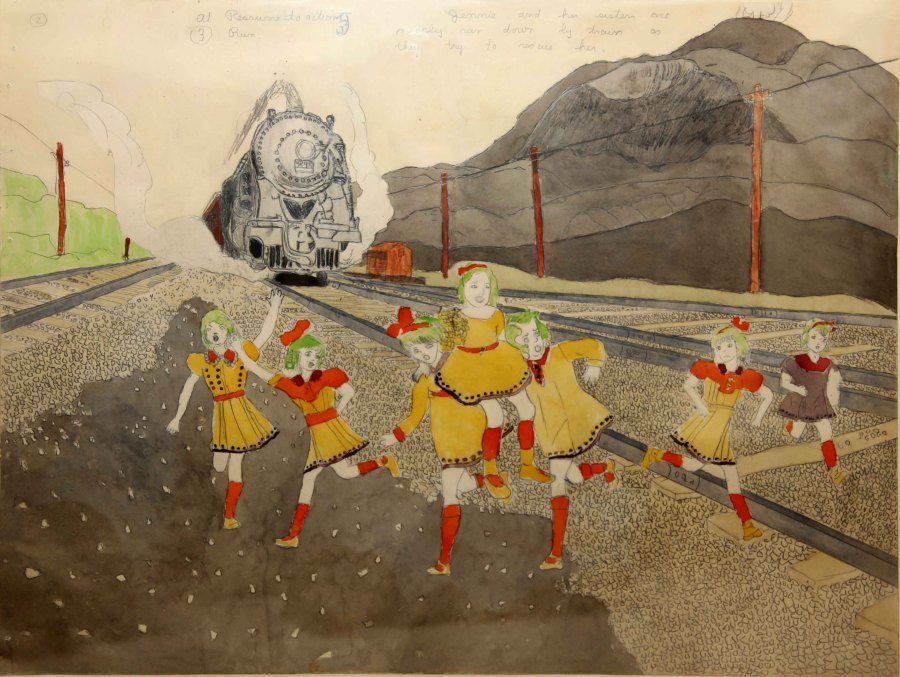

Henry Darger, one of the best-known American outsider artists, created collages in a Pop Art vein, cutting images out of coloring books, which resonated with viewers when they were discovered after his death in the 1970s. His works are on view via the Chicago gallery Carl Hammer.

The other therapy centers are Fountain Gallery, which is exhibiting bold geometric and erotic pen drawings by Anthony Ballard; the Gallery at HAI(Healing Arts Initiative) in Long Island City, Queens; Een Nieuwe Wind in Goes in the Netherlands; and Pure Vision of Manhattan.

“Untitled” (circa 1970-75), by an artist known as the Philadelphia Wireman. Credit Fleisher Ollman

“Untitled” (circa 1970-75), by an artist known as the Philadelphia Wireman. Credit Fleisher Ollman

Beyond this is a vivid range of work by self-taught artists from around the world, more plentiful than in prior years. One of the most amazing displays is of seven Czech artists at Cavin-Morris. They work mostly on paper, drawing abstract, mystical and botanically inspired designs. (Art by one of them, Anna Zemankova, was in the 2013 Venice Biennale.) Abstract pen drawings by Yuichi Saito are at Yukiko Koide. Manuel Lanca Bonifacio, a Portuguese artist in Britain who won an Outside In award in England in 2012 (yes, now there are outsider art awards), makes floating, figurative works, at Henry Boxer.

Some of the Haitian art collection of Jonathan Demme, the filmmaker, is on view at Arte del Pueblo. Andrew Edlin, the fair’s organizer, is showing the architectural works of Marcel Storr, a French street sweeper, at his gallery’s space. The Parisian dealer Hervé Perdriolle has works from India, and Galeria Estação from São Paulo has more standouts: Minimalist paintings of trucks by Alcides Pereira dos Santos, who was also a shoemaker, barber and stonemason.

“Untitled” (circa 2000) by Will Branch, from northern Mississippi. Artists from the South continue to play a prominent role in the fair. Credit The Pardee Collection, Iowa City, IA

“Untitled” (circa 2000) by Will Branch, from northern Mississippi. Artists from the South continue to play a prominent role in the fair. Credit The Pardee Collection, Iowa City, IA

Artists from the American South continue to play a prominent role. The Metropolitan Museum is adding 57 works from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, which is devoted to self-taught African-American artists, to its collection, and exhibiting them next year. From rural northern Mississippi, Will Branch and Emitte Hych are represented by bright figurative paintings at Pardee. At Shrine are sheet-metal and wood sculptures by the Rev. George Kornegay, an Alabama artist who makes outdoor environments. Arte del Pueblo is showing Minnie Evans’s crayon and graphite works from the 1940s. Ms. Evans lived in Wilmington, N.C., and was inspired partly byAirlie Gardens, where she worked as a gatekeeper.

Mary Whitfield, based in Birmingham, Ala., has paintings at Galerie Bonheur that depict violent scenes of lynchings and one of women, “Fleeing Darfur” (2006). Bruce Davenport Jr. is a New Orleans artist who draws marching bands in formation; his work is at Louis B. James. The art of T. A. Hay, a farmer from Kentucky who painted paper and gourds with brown shoe polish, is on view at Tanner-Hill. And from farther west is the work of Daniel Martin Diaz of Arizona, whose alchemic, cartoonlike drawings reveal his Mexican-American and Roman Catholic upbringing, at American Primitive Gallery.

This year’s fair includes a mini-exhibition, organized by Anne Doran and Jay Gorney, titled after the blues song “If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day,” by Robert Johnson. It displays pieces by a mysterious unknown, the Philadelphia Wireman — believed to be deceased — who made little sculptures, not unlike Ms. Scott’s, from wrapped, found materials; they were discovered abandoned in an alley. There are also entertaining oddities, like the vernacular photographs — police lineups, circus freaks, dental close-ups — at Winter Works on Paper of Brooklyn.

Despite many changes in the outsider world, diagnosis still reigns. You’re often told, when you inquire about artists, that they were autistic, schizophrenic or developmentally disabled. It makes you wonder what it would be like to be given the same information at other art fairs: about the artist’s depression, alcoholism or obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Perhaps as outsider and insider worlds continue to merge, we will see more nuance on that front: a Spectrum Fair, for those not flagrantly anything, but on the spectrum.

Creative Growth Featured in the Wall Street Journal

Arts + Entertainment The Inside Guide to Outside Art Five Artists to Watch at New York’s Outsider Art Fair

By Ellen Gamerman January 29, 2015

Now on view: work by artists who don’t know they’re artists.

The Outsider Art Fair, an international show of work by self-taught artists isolated from the mainstream, kicked off Thursday in New York. Even at a time when art in the world’s great museums can be found everywhere online, the fair argues that there is still such a thing as untouched genius.

Increasingly, insiders are hunting for outsider work. A fantastical watercolor and pencil piece by former hospital custodian Henry Darger sold for $745,000 at Christie’s last year, setting an auction record for the artist. Next year, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art will display a new donation of art by untrained African-American artists from the South that includes 10 pieces by outsider legend Thornton Dial.

Outsider art has become so popular that dealers are sharpening their search for phonies. “Sure, there are people trying to get on the train,” said Andrew Edlin, a New York art dealer who owns the fair. “Someone emails you saying, ‘I’m an outsider artist.’ That almost reflexively disqualifies you.”

Months before the fair, a vetting committee studies the artists on the roster to make sure they belong, Mr. Edlin said. “Sometimes an artist kind of looks outside, but then, ‘Hey, look what I found—an MFA,’” he said. While some artists may have received a bit of training, they largely are working on the margins, some grappling with poverty and mental illness.

Musician David Byrne is a fan of the genre. The former Talking Heads frontman commissioned art from the traveling Baptist minister and outsider artist Howard Finster for the 1985 album “Little Creatures.”

“I found the work hugely inspiring—straight from the dark, twisted heart that we all share,” he wrote in an email. The New Yorker’s purchases include drawings from a man outside a halfway house on his block and work by high-profile artists like Mr. Darger. “Some of the stuff I have I couldn’t afford now,” he said. Here are five artists not to be missed at the fair, which runs through Sunday.

Augustin Lesage’s ‘Untitled,’ circa 1943 PHOTO: GALERIE ST. ETIENNE, N.Y.

Augustin Lesage’s ‘Untitled,’ circa 1943 PHOTO: GALERIE ST. ETIENNE, N.Y.

Augustin Lesage Mr. Lesage is a Hall of Famer in the world of “art brut,” as outsider art is also known. The former coal miner from France attended séances and believed that voices, including one belonging to his dead sister, told him to paint. He went on to earn a living as a medium and artist before his death in 1954.

Adolf Wölfli’s ‘Untitled‘ PHOTO: ANDREW EDLIN GALLERY

Adolf Wölfli’s ‘Untitled‘ PHOTO: ANDREW EDLIN GALLERY

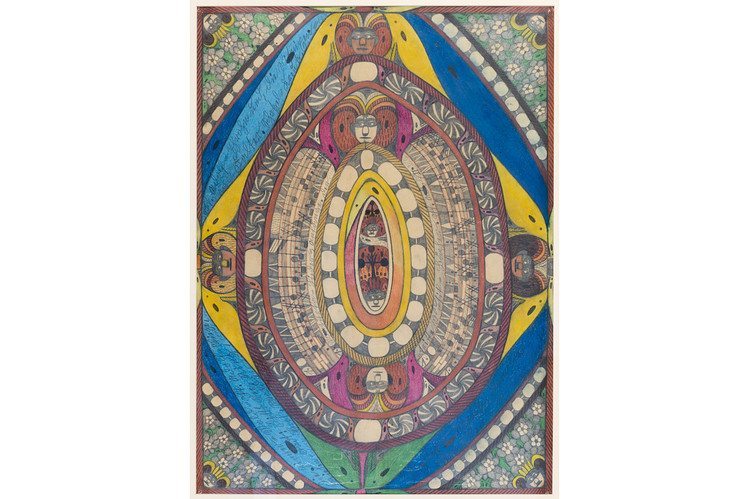

Adolf Wölfli The schizophrenic artist who lived in a Swiss mental institution for most of his adult life created mandala-like images featuring what appeared to be self-portraits—pictures of “St. Adolf II,” his alter ego who went on imaginary journeys. Much of the work on the market by Mr. Wölfli, who died in 1930, was what he called “bread art,” pieces he sold or traded for art materials.

Judith Scott’s ‘Untitled,’ 2003 PHOTO: CREATIVE GROWTH ART CENTER

Judith Scott’s ‘Untitled,’ 2003 PHOTO: CREATIVE GROWTH ART CENTER

Judith Scott The late artist, now the subject of a solo show at New York’s Brooklyn Museum, was born with Down syndrome and largely deaf. She was institutionalized for decades until the 1980s, when her twin sister moved her from Ohio to California. There, she found art, wrapping objects in yarn and other materials.

Susan Te Kahurangi King’s ‘Untitled,’ circa 1978 PHOTO: SUSAN TE KAHURANGI KING/CHRIS BYRNE

Susan Te Kahurangi King’s ‘Untitled,’ circa 1978 PHOTO: SUSAN TE KAHURANGI KING/CHRIS BYRNE

Susan Te Kahurangi King The 63-year-old New Zealand artist stopped speaking by the time she turned six. She returned to drawing in 2008 after abandoning it for nearly two decades. Her pieces, which made their New York gallery debut in a show by independent curator Chris Byrne at Mr. Edlin’s gallery last year, often depict a cartoon world gone awry.

Jerry the Marble Faun’s ‘Windsor,’ 2009 PHOTO: JACKIE KLEMPAY GALLERY

Jerry the Marble Faun’s ‘Windsor,’ 2009 PHOTO: JACKIE KLEMPAY GALLERY

Jerry the Marble Faun The onetime gardener at Grey Gardens goes by a nickname bestowed on him by one of the Long Island estate’s famously eccentric occupants. Work by the 60-year-old artist, who began carving dragon heads and other figures in marble, limestone and alabaster in the late 1980s, appears at the fair for the first time.

Creative Growth Featured in Huffington Post

Arts + Culture What Is The Meaning Of Outsider Art? The Genre With A Story, Not A Style

By Priscilla Frank January 30, 2015

If you've perused The Huffington Post Arts & Culture page at all this week, you may have noticed the spread of outsider artists gracing the site. That's because this weekend is the 23rd edition of the Outsider Art Fair, one of the rare and peculiar occasions when the art world gathers to celebrate and explore artists who, by and large, are unaware of the art world's real, prickly existence.

Henry Darger, Jenny and Her Sisters are Nearly Run Down by Train..., n.d. Watercolor and pencil on paper 18 x 24 inches (45.7 x 61 cm)

Henry Darger, Jenny and Her Sisters are Nearly Run Down by Train..., n.d. Watercolor and pencil on paper 18 x 24 inches (45.7 x 61 cm)

There are various ways to make sense of outsider art as a genre. Roberta Smith calls it "a somewhat vague, catchall term for self-taught artists of any kind." Lyle Rexer defines it as "the work of people who are institutionalized or psychologically compromised according to standard clinical norms" or "created under the conditions of a massively altered state of consciousness, product of an unquiet mind." Jerry Saltz argues it doesn't exist at all, except as a discriminatory boundary preventing untrained artists from their rightful places in the canon.

Rebecca Hoffman, director of the Outsider Art Fair, has her own distinction. "I utilize the term 'outsider art' as an umbrella for a lot of different categories," she explained to HuffPost. "Primarily, what we term outsider art is self-taught or non-academic work. So, that could be somebody who is a mathematician who has taught himself how to paint. That could be somebody who [has severe autism] and expresses himself through drawing. That could be a member of an aboriginal tribe in Western Australia, a herdsman for her entire life, who painted prolifically for her final 14 years of life. That could be someone who was drawing to escape violence in New Orleans. It could be someone who took to marble carving to express all of the diverse experiences he's undergone."

Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, c. 1978, Graphite, ebony and crayon on paper

Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, c. 1978, Graphite, ebony and crayon on paper

According to Hoffman's definition, which echoes the "catchall" mentality of Smith, the "outsider" classification hinges more on the artistthan the art. While other genres like Abstract Expressionism or Cubism denote a specific set of aesthetic guidelines or artistic traditions, the label "outsider art" reflects more the life story and mental or emotional aptitude of the artist. Outsider art lumps together a mishmash of people from wildly disparate places and times, similar only in the fact that they seem to struggle with a vague blanket of personal trajectories and inner demons.

Take for example the fact that a 19th century artist from rural Switzerland, diagnosed with schizophrenia after attempting to molest a young girl, is placed in the same category as a contemporary artist based in Oakland, California, whose watercolors take inspiration from Kiss and The Addams Family. How can this be?

To complicate matters even further, most artists on view don't categorize themselves as outsider artists, or even realize their work is being seen and evaluated at all.

"The art exhibited in our show was created out of a need to create art and a love for art, rather than art that's referencing cultural signifiers or informed by the institution or intellectual signifiers," Hoffman continued. It's this unifying aspect that often yields works that overlap aesthetically, despite the contrasting origins and experiences of the artists. Outsider art is, often, known to be naive, obsessive, visceral and autonomous -- dissociated from the artistic norms and trends that define the zeitgeist for those not impervious to it. After stripping away cultural conventions and the impending shadow of the artistic establishment, artists' deeper inspirations and messages come to the surface. And sometimes, oddly, they converge, hinting at some yawning humanity within us all.

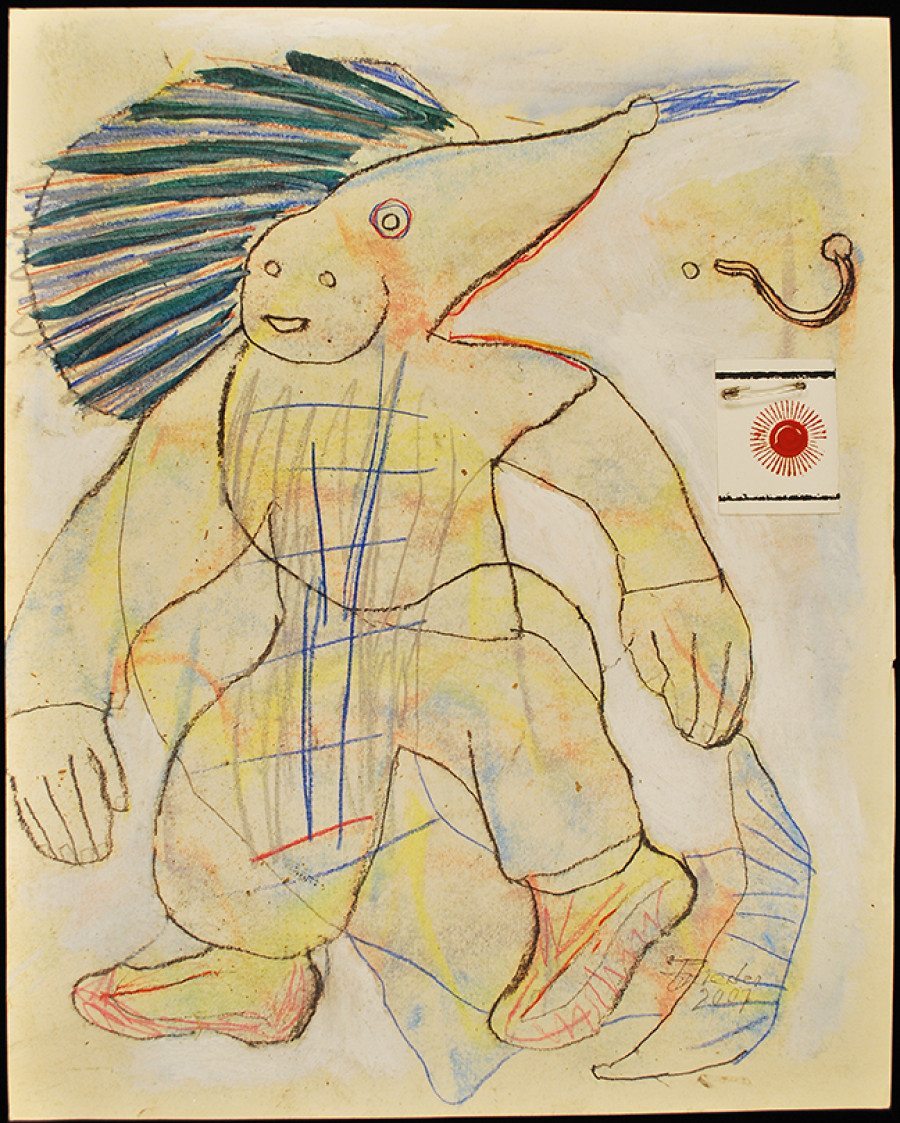

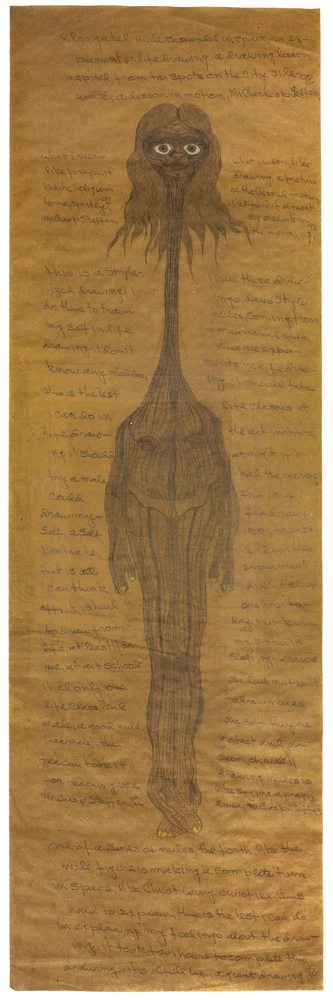

Andrew Frieder, Untitled (Fishman) 2007 mixed media on paper 20X16”

Andrew Frieder, Untitled (Fishman) 2007 mixed media on paper 20X16”

Certain words buzz around discussions of outsider art -- words like "naive," "pure," "raw," "visionary" and "fanatic." It's true -- we've used some of the above. While many of these characteristics hold true, they speak not only to the artist but the viewers, and their own ideas of what constitutes art making in its most idealized, authentic sense. Are they searching for the maniacal genius, isolated and misunderstood, creating beauty that stands outside of time and circumstance, untouched by the pettiness of everyday life and mainstream culture? After all, outsider art, at times, affirms the value and potential of art many artists and art lovers believe in and aspire to: it celebrates the outsider. It unveils the unadulterated act of creation, outside of norms and trends and anxieties and the desire for commercial success. It can conveys the power of the unbridled imagination to create order, constitute beauty from basically nothing and even save a life.

"Why look at outsider art and self-taught art, if not out of romantic nostalgia for some image of unfettered individuality and expressive freedom?" Lyle Rexer writes in How to Look at Outsider Art. "Or is our fascination with this art just one more form of voyeurism?"

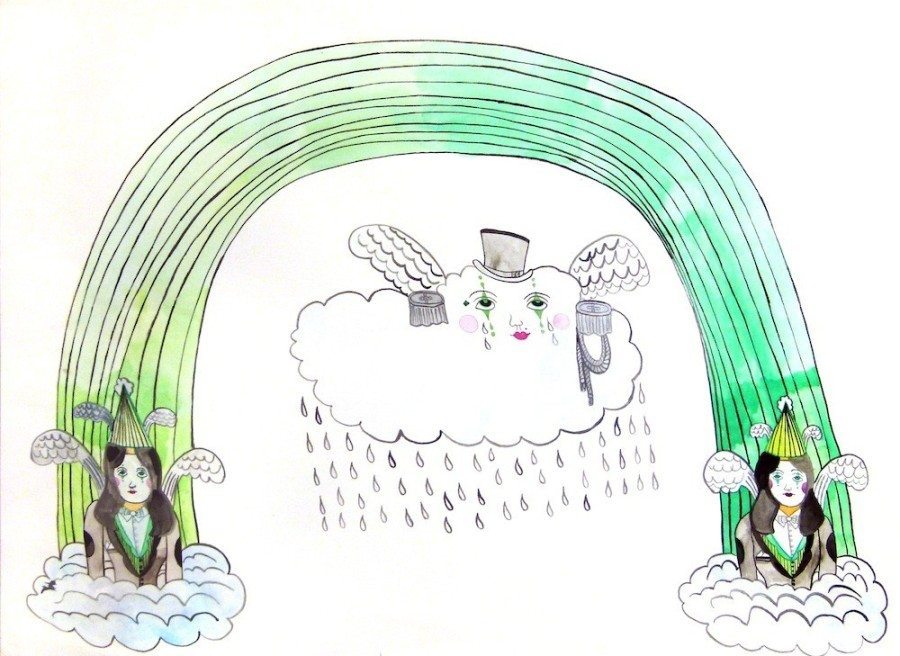

Aurie Ramirez, Untitled, 2009

Aurie Ramirez, Untitled, 2009

"I was basically born into the art world," Hoffman said. "My mother owns an art gallery and I grew up around art my whole life. I had reached a point where I got into the business of outsider art because I love that moment where a person clicks with a piece of art and falls in love with it. Maybe that's an old fashioned notion, but I wanted to have the opportunity to be involved with environments where people connected with art on a visceral level and all the other noise just stopped. I do think that happens more with outsider art. It's so pure in its need for creation."

The characteristics accepted as deep-rooted in outsider art often converge with what's praised in "insider art." Vincent Van Gogh famously grappled with mental illness, making his work all the more cryptic and all the more gripping. Yayoi Kusama, who's experienced hallucinations since a young age, said "Painting saved my life," and makes art to this day in a mental institution. Jean-Michel Basquiat's crude style, dubbed "primitivist" at the time, shot him to meteoric art stardom. Kinshasha Conwill, director of the Studio Museum of Harlem, explained in The New York Times: "People did exploit his race and try to make him an exotic figure."

Are outsider artists, à la Saltz's initial conclusion, victims of a similar reduction? Otherness, individuality and darkness have long been venerated in the world of art; so, are outsider artists the apotheosis of this kind of exploitation? Or does the veneration of outsider art further lay bare a reality that's simply slipped under the rug in other circles?

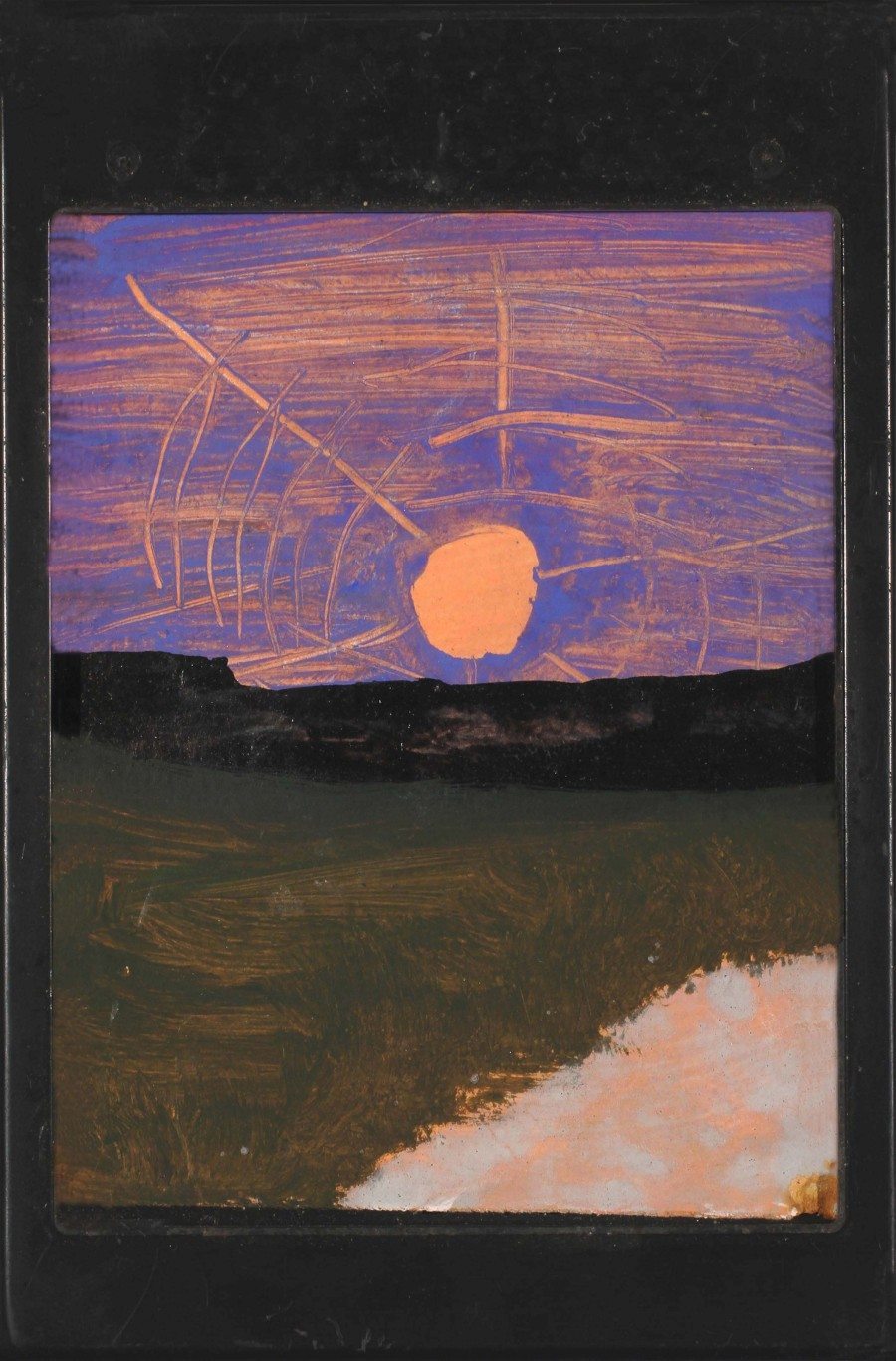

Landscape, Sunset over Black Mountain, Water color and oil on paper ( Polaroid box cover ), 3 13/16” x 3 ¼”

Landscape, Sunset over Black Mountain, Water color and oil on paper ( Polaroid box cover ), 3 13/16” x 3 ¼”

In the end, there is a dark side -- or at least a discomforting side -- to the quickly rising popularity of art explicitly made possible by suffering, whether of mind or physical circumstance. But there's also an undeniable magic to the ethos of the fair, a message that communicates that, at its core, art is by everyone and for everyone. It's not about clever allusions, MFAs, market trends and traditions that are constantly being overturned for the sake of overturning them. Through an outsider lens, art is about imagination and creation, generating worlds inside your mind and letting them free, transforming suffering into profound beauty.

Because of the simplicity of the message, outsider art is also refreshingly unpretentious. "You look at fairs like Scope or Pulse or the Armory show, and they're all showing work that has been created in a vacuum where people paid attention to the artistic institution, where people pay attention to art historical practice, the chronology of development," Hoffman said. "The Outsider Art Fair is more approachable. There's a large percentage of the population who may not feel comfortable going to Frieze because they do not know the institution. Here, everyone is welcome."

We should be careful about how we address, categorize and subconsciously idealize what's known as outsider art. But when it comes to seeing it in person -- as Hoffman is quick to point out -- we should never hesitate.

The Outsider Art Fair runs from January 29 until February 1 at Center 548 in New York. See a preview below and let us know your thoughts in the comments.

Adolf Wölfli

Adolf Wölfli

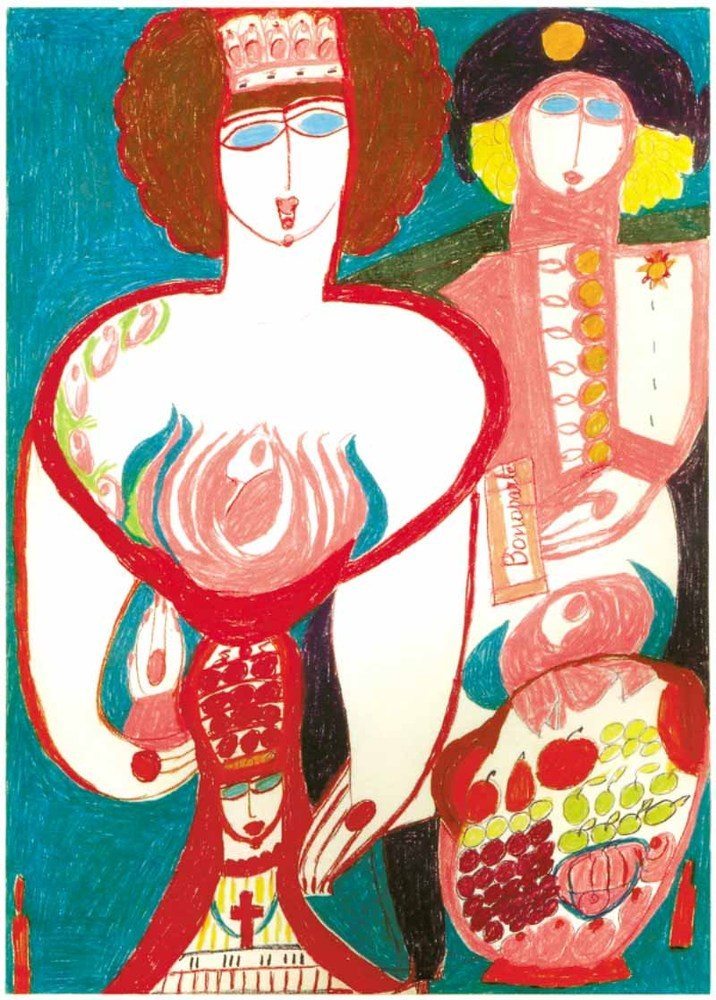

Aloise Corbaz

Aloise Corbaz

Brent Green

Brent Green

Carlo Zinelli

Carlo Zinelli

Charles Steffen

Charles Steffen

George Widener 'Titanic' 2012 ink on paper 48 x 48 in

George Widener 'Titanic' 2012 ink on paper 48 x 48 in

Creative Growth Featured in Art in America

Previews Five Points With Tom di Maria

January 30, 2015 by Chris Chang

Tom di Maria has served as the director of the Creative Growth Art Center since 2000. Prior to this position, he was assistant director of the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive at the University of California Berkeley. An award-winning filmmaker, di Maria has received prizes from Sundance, Black Maria, Sinking Creek, National Educational Media and New York Experimental film festivals. Creative Growth is participating in the Outsider Art Fair, on view at Center 548 in Chelsea (through Feb. 1).

1) For those that do not know, please explain the Creative Growth Art Center. It's the oldest and largest art center in the world for people with disabilities-primarily developmental. We have people on the autism spectrum, with Down syndrome, with different forms of mental retardation, with some kinds of brain injury and a variety of other disabilities. The center was founded over 40 years ago by Florence and Elias Katz, at a time when California was deinstitutionalizing people with disabilities. Creative Growth has never taught in a formal way. We're not art therapists or a provider of social services. We just say: Come here, find your way, find your voice and tell us your story. Take as much time as you need. There are now over 150 artists per week working with us.

2) Tell me a bit about your background, specifically in regards to how it relates to your present mission. I studied film and photography and worked at and directed various film festivals. In terms of my livelihood I was more successful as an arts administrator than an artist. I grew up in the age of AIDS and I saw how art could have a transformative social component, by helping people understand the world differently. When the last director of Creative Growth was retiring 15 years ago, I went there reluctantly, but found the place so compelling I couldn't leave. My first thought was, this is so different from a museum! It's not a temple of the object; it's a laboratory of aesthetics.

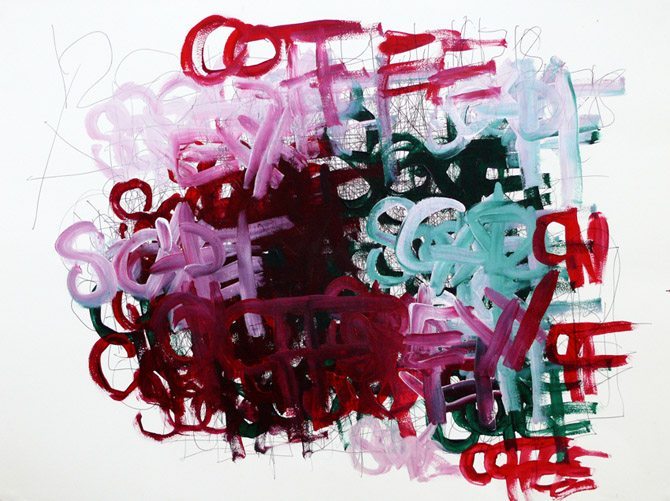

3) Judith Scott's show at the Brooklyn Museum [through Mar. 29] must be extremely important for you. I don't think our founders could have ever imagined that show. Her life parallels Creative Growth's history. The visibility of the Brooklyn show, and the fact that it takes place within the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, is simply phenomenal. We also now have three artists in MoMA's collection. Dan Miller was the first, and then Judith Scott and William Scott [no relation]. Judith was deaf but never diagnosed as such. She was never taught sign language or any other language. The work she did was a language substitute.

4) Not unlike Dan Miller. Some of our artists work with us for years, if not decades, before they achieve any level of success. Dan is a nonstop worker. He comes in five days a week. He's unable to travel by himself so we send a bus to pick him up. In addition to his severe autism, he has a significant seizure disorder and needs to wear a helmet. Dan has become more and more interested in the abstract quality of words. His early work, for example, might feature a drawing of something figurative, like a rabbit, with words next to it. He continued writing more and started to paint words on top of each other. People remark on the visual similarity to Cy Twombly's work, but with Dan it's important to note that the content comes first. Dan and Judith are trying to find ways to tell their stories when they have no verbal words. The process is an extremely obsessive yet necessary part of their lives. When the piece is done, the object has very little value for them. It's time to move on. Usually within five seconds the next piece is started.

5) You are in town for the Outsider Art Fair. Are your artists outsiders? No! They're people with disabilities. They've lived outside of society in so many ways and have been called so many names they don't need another label. The reason why we participate in the Outsider fair is because so many people from the art world with an interest in self-taught, non-academic art show up. Our artists' work responds to that interest. With all of our sales, 50% goes to the artist and the remaining 50% goes to the organization, which pays for the artists' studio spaces and art supplies. That's why it's important for us to attend the fair. But when I look into the room at Creative Growth and see a hundred or so artists working and living in the present moment, I don't think of them as outsiders. I think of them as contemporary artists.

Judith Scott

Judith Scott

William Scott

William Scott

Susan Janow

Susan Janow

Dan Miller

Dan Miller

Alice Wong

Alice Wong

"Judith Scott: Bound and Unbound" Featured in The New York Times | Review by Holland Cotter

ART & DESIGNART REVIEW

Silence Wrapped in Eloquent Cocoons

Judith Scott’s Enigmatic Sculptures at the Brooklyn Museum

By Holland Cotter December 4, 2014

Judith Scott’s sculptures sit like large, unopened, possibly unopenable bundles, contents unknown, in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. In a few, objects can be made out under layers of tightly bound string, rope and fabric strips: a child’s chair, wire hangers, and in one ambitious instance a not-at-all disguised shopping cart. Some pieces suggest the contours of musical instruments, or weapons, or tools. Most are irregularly rounded and sheathed in bright-color yarn. All untitled, they look like gift-wrapped boulders, though it’s hard to gauge their weight or what they might feel like to the touch. Heavy or light? Soft or hard?

You can identity all of them as abstract sculptures and stop there, though this leaves something vital out: clear evidence of a hand and mind at work, spinning out lines and colors as purposefully as expressive strokes in a painting. But expressing what? Mystery provokes speculation. Thoughts of ritual arise, and also of play. Craft associations are obvious, though unorthodox ones: of weaving without looms, knitting without needles. Images from science occur: of nests, circulatory systems, neural wiring. So do links with art history, including the history of fiber art, old and new, which has emerged largely from the hands of women.

Ms. Scott, who died in 2005 at 61, had an interesting history of her own. A twin, she was born with Down syndrome and consigned to a state institution in Ohio at the age of 7. Because she couldn’t communicate verbally, she was classified as “profoundly retarded.” Only in her 30s was it discovered that she couldn’t learn language because she was deaf. In the 1980s, her twin sister, Joyce Scott, became her legal guardian, brought her to live near her in the San Francisco area and enrolled her in an art workshop called Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland.

Creative Growth is an absorbing subject in itself. It was founded in Oakland in 1974 by an artist, Florence Ludins-Katz, and her husband, a psychologist, Elias Katz, as an art workshop for physically and developmentally disabled adults. Operating somewhere between art therapy and a full-on art studio program, the workshop provides materials, professional instruction, and a communal environment, but encourages people enrolled there to work in their own way at their own pace.

Ms. Scott was 43 when she arrived in 1987. She first took up painting and drawing. Several early works on paper are in the show, most of all-over looping, bubblelike patterns done in colored pencil. After a year, she joined a class run by a fiber artist, Sylvia Seventy, and found her chosen medium when she tied a cluster of wooden sticks together with yarn, twine and cloth, attached some beads as embellishments, and — for the first and last time in a sculpture — added paint.

That piece is in the Brooklyn show, organized by Catherine Morris, curator of the Sackler Center, and Matthew Higgs, director of White Columns in Manhattan. And it established a model she would periodically return to, but also elaborate on and depart from. Within a few months, she was making vaguely anthropomorphic forms from multiple wrapped clusters connected with networks of red, green, yellow and purple fabric. And from the start, her sense for color was subtle and acute. In a wings-shaped sculpture from 1989, passages of orange, red and black yarn overlap, seeping into each other in a molten way, like lava.

Ms. Scott made this work, as she did everything, while sitting at a large table. And many early pieces are tabletop flat and could easily hang, like paintings, on a wall. (She never indicated any preference in matters of display.) The sculptures gradually became more complicatedly three dimensional, with branching and bending extensions. In the 1990s, she concentrated on densely swaddled and intricately knotted cocoons and pods that took weeks, sometimes months of steady effort to complete. In some, half-submerged found objects are teasingly visible; others seem to be entirely nonreferential. And as in some of the paper and fabric collages of the New York modernist Anne Ryan, what you keep coming back to is color, texture and a witty, swirling, adventuring hand-madeness.

A flat spoon-shaped piece from 1993 is covered with tufts of multicolored yarn, as it were sprouting flowers. Another, from a year later, looks at first like a heap of random cloth scraps but turns out to be a study in brown, beige and white as well as a compendium of textile types at her disposal: silk, velour, flannel, cotton, denim and something sheer.

Now and again, satiny ribbons add glamour. (Judging from photographs, Ms. Scott was a majestic dresser, partial to turbans and jewelry.) And unlikely ingredients are put to good use. A length of baby-blue industrial tubing turns a flat-topped cocoon into a miniature version of the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing. Although her materials were pretty much determined by what was in stock at Creative Growth at any given time, what she did with what she had was her decision alone, and the decisions were genius. Once, when supplies ran low, she gathered paper towels from a kitchen or bathroom at the center, ripped and twisted the sheets and knotted them together to make her single entirely monochromatic sculpture, an image as pacific and alert as a nesting bird.

Was it meant to be an image? Or monochromatic? Or even something called sculpture? The issue of intention, or lack of it, was at one time a factor used to define and isolate the “outsider artist,” particularly if that artist had mental disabilities. The assumption was that insider artists rationally decide what they are going to do and do it, while outsiders, incapable of self-direction, produce like automatons, compulsively. This is a mistaken view of both sides of the divide, yet the divide itself, for better or worse, continues.

And since it does, the question remains of where, in the concept of outsider art, the stress should fall: on outsider or on art? The show’s intelligent catalog addresses this. In an essay, the art historian Lynne Cooke pointedly avoids the reference to biography in writing about Ms. Scott and instead places her work in the larger context of formally related contemporary art. By contrast, an interview by the poet Kevin Killian with the artist’s sister, Joyce, is almost entirely about biography and makes serious attempts to understand Judith Scott’s art though that lens. In the end, both approaches by themselves fall short, but taken together, and kept in balance, are valid and reconcilable. It is from that balance that Ms. Scott emerges as the complex and brilliant artist and person she was.

“Judith Scott: Bound and Unbound” remains through March 29 at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, at Prospect Park; 718-638-5000, brooklynmuseum.org.

"Judith Scott: Bound and Unbound" Featured in The New York Times | The Opinion Pages

The Opinion Pages An Artist Who Wrapped and Bound Her Work, and Then Broke Free

December 1st, 2014 By Lawrences Downes

Some of Judith Scott's artwork at the Brooklyn Museum. Credit Bebeto Matthews/Associated Press

Some of Judith Scott's artwork at the Brooklyn Museum. Credit Bebeto Matthews/Associated Press

Judith Scott was an artist based in Oakland, Calif., who made abstract works from fiber and found objects. Some of them are small and slender, like a hunter-gatherer’s quiver. Some are large enough to cradle in both arms. Some you would need a shopping cart to move. One actually is a shopping cart, piled high with seemingly random objects and cocooned in white string.

That piece and many others are on display through March at the Brooklyn Museum in “Bound and Unbound,” a comprehensive survey of Ms. Scott’s art. The title is apt. Ms. Scott’s method was to use yarn, string and knotted fabric to wrap mundane materials, like crutches, bicycle wheels and plastic tubing, to the point of transformation. The shrouded objects are often left unrecognizable. The results are bafflingly beautiful.

Some works once reminded a Times critic of “the animal-shaped kono power objects of the Bamana people of Mali.” But it’s safe to say of Ms. Scott’s art that the Bamana people have nothing to do with it, and that any detected symbolism or allusion is a viewer’s projection.

To watch an excerpt from “Outsider: the Life and Art of Judith Scott,” a film by Betsy Bayha, Icarus Films, please click here.Ms. Scott had no formal training, no education to speak of, could not hear or speak and had Down syndrome. Her work exists without explanation, even as to how it should be displayed. Right-side up or down is a curator’s assumption. Every one of her 200 or so pieces is “Untitled.”

The art world does agree that the works are superb. They are shown around the world, the subject of articles, books and films. On film, you can see Ms. Scott spooling, cutting and knotting with a quilter’s patience and a genius’s dedication. She would work until her fingers were stiff and bleeding, motivated by who knows what. “Some mysterious personal juju” is how the musician David Byrne, an admirer, put it, acknowledging that it is impossible to know what was going on behind her watery eyes.

As a child, Ms. Scott was declared profoundly retarded and ineducable. At 7, she was sent to a state hospital in her home state of Ohio. She was institutionalized for 35 years. She got out only because her twin sister, Joyce, living in the Bay Area, missed her and became her guardian. In 1987, Joyce took Judith to Creative Growth Art Center, an innovative studio in Oakland for people with developmental disabilities. After nearly two years there, dabbling uninterestedly with paint, Judith found her medium.

She also found respect and deference as her talent blossomed. She became “very regal,” Joyce said, the queen of the place, with her own table and a wealth of supplies. As she wrapped her pieces — summoning the staff to remove them when she was done — she also made an artwork of herself, with colorful scarves and hats and strands of jewelry. A short documentary,“Outsider,” shows her as a woman of warmth and teasing affection in a close web of family, colleagues and friends.

Such dignity through achievement is too often the exception for people with Down syndrome, whom society prefers to infantilize and ignore. People with mental disabilities are easily pitied but seldom listened to; in the broader struggle for civil rights they remain a forgotten group.

Timothy Shriver, the chairman of Special Olympics, writes in a new book, “Fully Alive,” that people with intellectual disabilities bring those who are “normal” face-to-face with their own limitations. “In a world where we strive for independence and self-sufficiency,” he writes, “people with disabilities remind us that we are all dependent in some way.” The impulse has long been to hide these reminders away, locked in institutions or overlooked within families, sequestered from their own potential.

Sometimes, rarely, one among them hits the cosmic lottery and breaks through on her own.

Judith Scott became an artist in her early 40s. She was 61 when she died, in 2005. Her artistic vision, like all genius, is a mystery, but what made it possible is simple to explain: her own hard work, the love of a sister, the attentive support of a groundbreaking arts institution — and miles and miles of string.

Ms. Scott’s pieces are colorful, oddly shaped yet graceful, unself-consciously beautiful. That is also a good way of describing a human being, which Ms. Scott — against overwhelming odds, and the larger world’s denial, and without saying a word — declared herself to be.

______ A version of this editorial appears in print on December 2, 2014, on page A26 of the New York edition with the headline: An Artist Who Wrapped and Bound Her Work, and Then Broke Free."Judith Scott: Bound and Unbound" Featured in The New Yorker

The New Yorker Art | December 1st 2014 Issue

WRAP STAR

“Judith Scott: Bound and Unbound” at the Brooklyn Museum

By Andrea K. Scott

A fibre-and-found-object sculpture from 2004 by Judith Scott. Like all her works, it is untitled.

CREDIT COURTESY SMITH-NEDERPELT COLLECTION AND CREATIVE GROWTH ART CENTER; PHOTOGRAPH: BROOKLYN MUSEUM

A fibre-and-found-object sculpture from 2004 by Judith Scott. Like all her works, it is untitled.

CREDIT COURTESY SMITH-NEDERPELT COLLECTION AND CREATIVE GROWTH ART CENTER; PHOTOGRAPH: BROOKLYN MUSEUM

The best sculptures are trojan horses, staging sneak attacks on the status quo, from Marcel Duchamp’s readymade snow shovel to Franz West’s ingenuities in plaster and papier-mâché. The American sculptor Judith Scott literally concealed things: each of her cocoonlike constructions began with an objet trouvé—an umbrella, a skateboard, a tree branch, her own jewelry—around which she wound layers and layers and layers of yarn, twine, and strips of textiles until the item’s identity was obscured. She made sculptures with secrets. These magnificent fibre-wrapped works are now at the Brooklyn Museum, in “Bound and Unbound,” a show curated by Matthew Higgs and Catherine Morris.

Scott died in 2005, at the age of sixty-one, and didn’t start making art until her mid-forties. She was born with Down syndrome, went deaf as a child, and never learned how to speak. Languishing in an institution in her native Ohio for more than three decades with her deafness undiagnosed, Scott was considered so beyond help that she wasn’t allowed to use crayons. In 1986, her fraternal twin, Joyce, brought Scott to San Francisco and enrolled her in Creative Growth, a community art center for disabled adults. At first, Scott dabbled in drawings. A smattering are in the show, but they’re no match for the radical beauty that followed, when Scott took a textile workshop and had a breakthrough, loosely binding sticks into an uncanny totemic cluster. As her work gained complexity, the Bay Area began to take note; by 2001, Scott had been the subject of major shows in Switzerland, Japan, and New York.

Scott’s first sculpture is among sixty pieces now commanding attention in two rooms at the museum, installed in groups on low plinths. Although she worked autonomously, unaware of affinities, Scott’s pieces do have kindred spirits, from West’s nonideological sculptures to the medicine bundles of the Plains Indians—objects in which mystery becomes its own meaning. ♦

On View From October 24, 2014–March 29, 2015

Creative Growth Featured in Art Practical

Shotgun Review Creative Growth vs Anne Collier / Trisha Donnelly / Chris Johanson / Nate Lowman / Laura Owens By Anton Stuebner September 24, 2014

On View Creative Growth Art Center July 10 - August 15, 2014 Group Show

What does it mean to “author” a work? And how does an artist’s creative practice both engage with and react against the work of others? The 40th anniversary exhibition at Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, Creative Growth vs Anne Collier / Trisha Donnelly / Chris Johanson / Nate Lowman / Laura Owens, raises these questions through work that investigates—and confounds—assumed limits of collaborative practice and authorship.

Since its inception, Creative Growth has provided a space for artists with developmental, mental, and physical disabilities to produce new work through open access to materials and instruction. The oldest and largest art center of its kind in the United States, its program inspired similar centers for artists with disabilities both domestically and abroad.

For its 40th anniversary, Creative Growth invited White Columns director Matthew Higgs, a longtime supporter, to curate an exhibition of work produced on site in conjunction with five artists based in New York. The concept was straightforward: Higgs commissioned each artist to produce a black-and-white image, which was then screen-printed in an edition of fifty. Next, these prints were presented to the artists at Creative Growth. The artists were instructed to select a print and were given no formal directives other than to respond to the image on the paper. The unframed hand-worked prints were hung with binder clips and nails in a grid against two walls, with no identifying labels.

Higgs described the final works as “collisions,” and in viewing the pieces at once, the metaphor is apt. Without the familiar cues (placards, text) to guide the eye, the sharp juxtapositions between prints of colors, shapes, and hues create a field of constant visual rupture. That sensorial assault effectively explains the exhibition’s title, the preposition “versus” indicating a violent contrast, even resistance, between two opposing forces.

Each print becomes, in effect, a test case in the limits and/or possibilities of collaborative image making. A few of the artists reject outright the base image: John Mullins, for example, all but ignores Trisha Donnelly’s black-and-white photo print of a clouded sky, covering it with his own full-color painting of a bridge during rush-hour traffic. By contrast, Cedric Johnson’s over-paint of swatches of green and red between the arcs of Nate Lowman’s bull’s eye (a sly reference to his own “bullet hole” installations) plays on Lowman’s use of line and numerology, the layers of abstract color fields covered with handwritten equations that engage with the original’s use of numbers while still preserving its integrity.

In eschewing conventional notions of collaboration, these works raise questions about genealogies of making and the ways in which practitioners both consciously and unconsciously engage with the work of other practitioners. The horizontality of authorship here, however, owes less to appropriation and more to mash-up cultures in music. In the end, the presumed boundaries between one practitioner and another—as well as the presumed boundaries between the “disabled” and “able-bodied”—become blurred. The sum of the collision is greater than its parts.

The Artful Lodgers

The Artful Lodgers