Cleansers for a Cause

By Carolyn Forte

September 1, 2017

Dan Miller Featured | Folks Magazine | July 2018

The Painted Words Of An Autistic Art Star The text-based paintings of artist Dan Miller allow him to express the depths of his heart far more vividly than words ever could.

By Carey Dunne July 25, 2017

“STOP SAYING THE R-WORD,” reads a screen-printed poster that hangs in the window of Creative Growth Art Center, a nonprofit organization housed in a former auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland, California. In the center’s studio, artist Dan Miller hunches over a table covered in brushes and watercolor paper and begins to paint the alphabet. In blue acrylic that matches the blue hockey helmet he always wears, he scrawls a giant A, B, C, D, layering letters atop one another until they’re no longer legible. While he works, he chants cryptic phrases that sound like zen koans or fragments of experimental poetry: “Pull the light bulb from the socket? No,” he says. “Alphabet cookie, homemade cookie, right? Pull it gently, gently, right?”

“Right,” says Creative Growth staffer Kathleen Henderson. When Dan gets to Z, she hands him a fresh sheet of paper. Without taking a breath, he picks up a ballpoint pen and starts a round of furious scribbling. “Click, click, click,” he chants. “Click, click, click.”

Born in 1961 in Castro Valley, California, Dan was diagnosed with autism in early childhood. As he struggled with verbal communication, drawing became his primary mode of expression.

“From the time I can remember, Danny always liked to draw,” Cara Miller, Dan’s sister, told Folks. “He would draw on anything when we were kids. Inside books, on scrap paper, anything.”

As Dan was growing up—in an era in which people with disabilities were often institutionalized—his relatives never suspected that this compulsive drawing habit would someday propel him to art stardom. But they did invest significant time in his education: As a child, in addition to attending special education classes and summer camps, Dan spent hours every night working on reading and writing with his mother and grandmother, both schoolteachers. “Our grandmother was very dedicated to educating him above and beyond what he was getting at school,” Cara says. “Our Mom was always looking for tools and things that would help him learn—so he could learn to type, she got him one of the first portable computers ever made, which he still has.”

When he wasn’t drawing or typing, Dan obsessed over tools and mechanical things, poring over his father’s catalogs for Grainger’s hardware, or taking apart clock radios, overhead fans, and light bulbs. This fascination with mechanics, as well as his ritualistic childhood writing practice, now shows up as motifs in Dan’s artwork, which weaves fragments of memory into abstract compositions. (Words like ‘‘socket,’’ ‘‘light bulb’’ and ‘‘electrician’’ recur in his paintings.)

Almost twenty years ago, at the recommendation of a caseworker at his residential program, Dan started working out of Creative Growth Art Center. Founded in 1974 by a psychologist and an educator in their Berkeley garage, Creative Growth now provides studio space and gallery representation for more than 160 artists with physical, mental, and developmental disabilities.

With the guidance of staffers at Creative Growth, Dan’s scrap paper drawings evolved into wall-sized paintings, which eventually made their way into the elite reaches of the fine art world. Now, Dan is one of the best-known artists working out of Creative Growth. His work is included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. He’s had solo exhibitions at renowned galleries like Ricco Maresca, Galerie Christian Berst, Paris, and White Columns, New York. In a collaboration with Creative Growth Dan’s marker drawings even found their way into Vans stores as a series of unique limited-edition skate sneakers. His works sometimes sell for tens of thousands of dollars apiece.

Dan’s dense tangles of dark lines sometimes recall Cy Twombly’s demented cursive, and his scrawled phrases echo Jean-Michel Basquiat’s graffiti-inflected compositions. (“Rocketship pain,” reads one painting, in dripping black letters. “COFFEE COFFEE COFFEE,” says another. “ROOF HOUSE CARPENTER ELECTRICIAN” reads another, inside a childlike line drawing of a house with a pointed roof.) But any apparent stylistic mimicry is coincidental: Like most of his fellow Creative Growth artists, Dan never formally studied art. Instead, he works from what seems like an intense physical compulsion: Drawing seems a requisite bodily function, an instinct it would be unwise to suppress.

“He really doesn’t like to be without something to work on,” Kathleen says. “He’s always drawing. Because he works so much, things really have a magisterial mark.” Watching Dan work, you get the sense that, if the paper supply were to run out, momentum might propel him to start drawing on the surface of the table, the floor, the walls. “When he comes over, I know my pens and paper of any kind are subject to being hijacked,” Cara says. “We’ve learned to get our pens and regular paper in bulk from Costco. I make sure to have some stocked at all times.”

Contemporary art critics, gallerists, and psychologists of creativity have thoroughly expounded on the significance of Dan’s work, which, according to Bay-Area poet Kevin Killian, “achieves a clattering poetry of infinite discrimination.” Some comment on how his text-based paintings appear to deconstruct language; others speculate on the level of intentionality behind the artist’s methods. But as with any art worth looking at, his practice contains a big element of mystery, sometimes best left unspoiled by over-analysis.

“His work kind of speaks for itself,” Cara says. “It’s still difficult to really know what is happening in his head and heart, other than the basic things. It must be so hard for him to not be able to tell us things, to express what he is feeling and to tell us what he wants, aside from some of the basic things in life. I do believe that he has the desire to connect with people and to express himself.”

Art has helped him do that: “Creative Growth is the key-master that opened some of those doors for him. Danny’s life and the challenges he faces go well beyond what most people see,” Cara says. “Creative Growth and the people in it are some of the best parts of Danny’s life. That, and hamburgers. He loves hamburgers.”

This is part four of four of Folks’ series of profiles of some of the amazing artists at Oakland’s Creative Growth Arts Center, which serves artists with developmental, mental and physical disabilities.

For original article, visit folks.pillpack.com.

John Hiltunen Featured | Folks Magazine | July 2017

Keeper Of His Own Animal Kingdom John Hiltunen, who has diabetes and dyslexia, never made art at all until he was 54. Now his weird and wild collages are the toast of the art world.

By Carey Dunne July 7, 2017

Wearing starred-and-striped suspenders over a white t-shirt, artist John Hiltunen points to a small chest of drawers next to his workspace, housed in a cavernous former auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland, California: “Bodies go in this drawer; heads go in this one,” he says. Piled on his desk are glossy magazines—Vogue, GQ, Glamour, National Geographic—plus animal-themed wall calendars and patterned wallpapers.

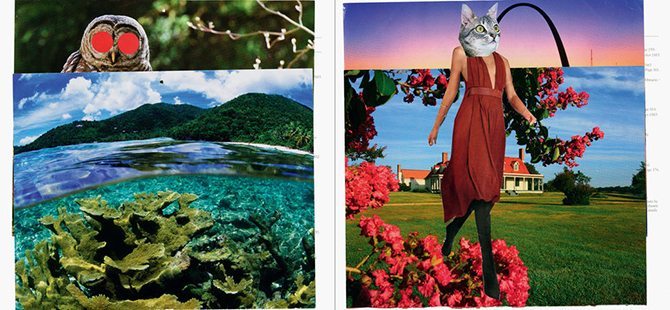

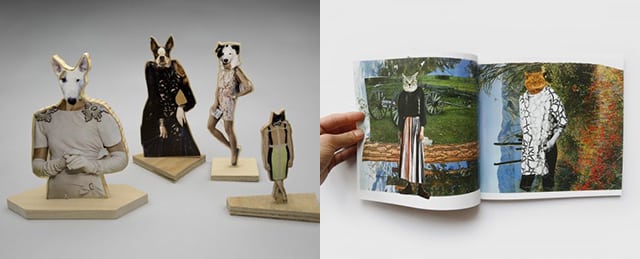

Working out of Creative Growth Art Center—a nonprofit that serves more than 160 artists with developmental, mental, and physical disabilities—John spends hours decapitating images of fashion models with scissors, then affixing their bodies to cut-outs of animal heads. Placed against scenic backdrops, these stylish chimeras fuse self-serious, airbrushed fashion photography with animal kingdom oddities: A guinea pig struts in a sequined tunic; a snowy owl carries a leather handbag through the woods; a ginger cat models a silk ball gown; a Yorkshire terrier strikes a pose in a frilly white pantsuit.

Since joining Creative Growth in 2003, John has become an unlikely art world darling. His animal-human mashups are routinely featured in contemporary art fairs like NADA Miami, the Independent, and Frieze New York. Talking Heads frontman David Byrne and artist Cindy Sherman are among the high-profile collectors of his work. In 2012, John’s work was the focus of a major group exhibition at Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco. In New York, he’s exhibited at White Columns Gallery and Rachel Uffner Gallery.

He got a late start: Until age 54, “I had no idea that I could do art,” John says.

Until age 54, “I had no idea that I could do art,” John says.

Born in Sturgis, Kentucky in 1949 and raised in Omaha, Nebraska by his cement contractor father and homemaker mother, John has struggled with severe learning disabilities since childhood. “My mom supported me a lot, but I never had any education,” he says. “I had problems with my eyes and with dyslexia. A bad case of that. Every time I tried to learn to read, I got a bad headache.”

When John was ten, his father died. After that, “everybody was telling my mom to send me away,” he says. “Back then, they thought it was a good idea to send disabled people away.” Eventually, his mother sent him to an institution in Brownsville, Texas. “They started giving me a lot of pills, drugging me a lot,” he says. “I really didn’t care for it. I remember being all druggy. I got to a point where I just didn’t take the pills. I’d hide them in my mouth and spit them out. They didn’t know that. They weren’t treating people right. So I finally called my mom and told her about it and she got me out of there.”

John moved to the Sara Center, a residential center for people with disabilities in Fremont, California, and stopped taking medications, except to manage his diabetes. Compared to the hellish institution in Brownsville, Sara Center was idyllic. There, he met his wife, Carol. “Basically, it was love at first sight,” he says. “We were married up on a hill.” At Sara Center, the couple lived independently, “getting along real well.”

But for decades, “I didn’t have any hobbies,” John says. “[I was doing] nothin’ much, just sitting in the house, watching TV, getting bored. I never really looked at art.”

That changed in 2003, when a friend referred John and Carol to Creative Growth. There, John discovered woodworking, rug-making, and ceramics. He and Carol also found a solid group of friends, who call him “Grandpa.”

“John’s kind of the patriarch in the community,” Creative Growth studio manager Matt Dostal says. “He brings in elaborate lunches for everybody in his friend group—a big cooler full of huge amounts of fried chicken and potato salad and diet Cokes.”

At first, John was critical of his visual art, and didn’t feel like he had a natural knack for it. But in 2007, visiting artist Paul Butler brought his traveling “Collage Party” to Creative Growth, inviting the artists to participate in a day-long cutting-and-pasting frenzy. “Collage can be really accessible for people who have a hard time drawing or painting,” Dostal says. “It’s a good gateway practice.”

At Paul Butler’s Collage Party, John made his first animal-human mashup. It was an instant hit. Fusing fashion and animal photography became his go-to practice. Though most of his works are variations on this same theme, they’re never formulaic; each collage introduces an exotic new hybrid species. His creatures often look somehow more natural than the chiseled, Photoshopped bodies that fill the pages of glossy magazines; it’s as if John is on a mission to tear off fashion models’ suffocating human masks and free the wild animals hiding beneath.

John is on a mission to tear off fashion models’ suffocating human masks and free the wild animals hiding beneath.

“His collages are in some ways incredibly simple, but there’s a really elegant subtlety, thoughtfulness and humor to the way he cuts out the images,” Dostal says. “They look so happenstance and poetic.”

“I just like switchin’ things around,” John says when asked why he gravitates toward collage. In recent years, John has expanded his practice to include 3-D art books and animated video pieces, such as “A Call to Kill,” in which an Australian Silky Terrier driving a sports car thwarts a villain’s plot to blow up the Golden Gate Bridge. Most recently, John had a solo show at Good Luck Gallery in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, where four pieces sold within the first two hours of the opening.

The success hasn’t gone to his head. “He doesn’t care what people think,” Dostal says. “He just wants to create his art.”

On June 14th, John and Carol celebrated their thirtieth wedding anniversary. “I’ve had a good life,” John says. He recalls how, in 2013, after being nominated by esteemed British curator Matthew Higgs, he won the Tiffany Grant—a biennial award given to American contemporary artists who demonstrate unique “talent and individual artistic strength” but haven’t yet received widespread recognition. Selected by a jury composed of artists, critics, and museum professionals, awardees receive an unrestricted check for $20,000.

John spent his prize money on a three-day trip to Disneyland with his wife and all their friends.

This is part two of four of Folks’ series of profiles of some of the amazing artists at Oakland’s Creative Growth Arts Center, which serves artists with developmental, mental and physical disabilities.

For original article, visit folks.pillpack.com.

Ray Vickers Featured | Folks Magazine | June 2017

The Illustrated World Of An Autistic Superhero-Artist Ray Vickers' one-of-a-kind comics, which feature teddy bear ninjas and sword-wielding bunny superheroes, have become highly-prized by art collectors. But for Ray, they're a way of making sense of the world.

By Carey Dunne June 28, 2017

Wearing a scorpion suspended in a glow-in-the-dark pendant around his neck, artist Ray Vickers sketches a picture of a rabbit wielding a sword made out of a carrot and tells me the legend of his own birth: “I was born with a tail, and with clothes on,” he says. “Red boxers, a white t-shirt, and a tattoo that said ‘Don’t Fuck With the Baby.’”

Coloring the carrot-sword orange, Ray tells me he can time-travel, that he’s Albert Einstein’s stepson, that he only ages once every 300 years. When he was a kid, he says, his tail let him hang and swing from things, until the fateful day it was bitten off by a pack of rabid dogs: “May it rest in peace,” he says.

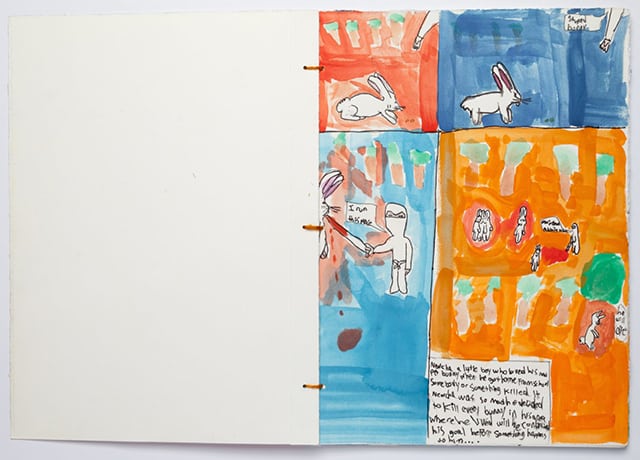

As one of 160 artists working out of Creative Growth Art Center—a nonprofit that provides studio space and resources for artists with developmental and physical disabilities in Oakland, California—Ray channels his wild imagination and sharp surrealist humor into drawing.

“Art helps me with my anxiety,” says Ray, 29. “It helps me to not focus on the stuff I’m going through. It helps me escape reality. I like to live in my own world twenty-four-seven. You can’t get in trouble if you live in your own world.”

The illustrated world Ray has created since joining Creative Growth in 2009 is filled with anthropomorphic rabbit-heroes and teddy bear-villains, pop culture icons like Captain America, and graphic motifs like eyeballs, eight-balls, and arrows.

As a comic book-obsessed student at Oakland’s Stonehurst Elementary School—which he describes as “H-E-double hockey sticks”—Ray often drew superheroes while bored in class.

“When I was young, but old enough to understand, my mom explained what I had: Autism, Asperger’s, dyslexia, ADHD,” he says. “We’re not stupid, we just learn differently than others. I always knew I was different, but didn’t know I could make money selling art.”

“Art helps me with my anxiety… It helps me to not focus on the stuff I’m going through.”

Growing up in southeast Oakland in the nineties, Ray often saw the impulse to “escape reality” play out in drug and alcohol abuse. Having witnessed the toll this took on his community, he swore he’d “never smoke, drink, or vape.” Instead, he sought escape through reading DC and Marvel Comics, watching action movies, volunteering at the Oakland Zoo, and attending cosplay and toy conventions. “Toys are my drug,” he says, showing photos of his vast collection of action figures.

As a teenager, when he wasn’t attending Richmond Educational Learning Center, studying Independent Living Skills at Alameda College, or working as a handyman with his cousin, Ray “was just chilling constantly at home with [his] leopard gecko, watching Spiderman cartoons from the eighties.”

It wasn’t until 2009, when his case manager referred him to Creative Growth, that Ray found the resources he needed to develop his art practice. Superhero doodles soon evolved into works that have been shown in established galleries and major art fairs, including the NADA Art Fair in Miami and the Outsider Art Fair in New York.

“I always knew I was different, but didn’t know I could make money selling art.”

At Creative Growth one morning, Ray works alone in a quiet back room of the former auto-repair shop, drawing with Sharpie, listening to Nine Inch Nails on headphones. He describes his work-in-progress: “This rabbit’s looking at his carrot sword, trying to decide if he’s gonna kill the teddy bears,” he says. “The teddy bears killed his family and friends, because they were discriminating. Now he’s trying to decide what’s next in life.”

In recent years, Ray’s drawings of dead rabbits have earned something of a cult following. “He drew a dead rabbit one day, people loved it, and it sold very quickly,” Creative Growth Studio Manager Matt Dostal says. “It became a motif for him. Now he does these rabbits with carrot samurai swords beheading stuffed animals, a lot of funny comic violence.” In 2015, Ray’s series “Newcha’s Revenge Against Bunnies Bunny Revenger” was shown in a group exhibition at the renowned Fraenkel Gallery, curated by artist Katy Grannan.

In April, in preparation for Creative Growth’s annual fashion show and fundraiser, Ray spent months crafting an army-green suit with a matching mask and gauntlets made from shin guards, plus a bow and a quiver for arrows. This costume transformed him into Green Arrow, a superhero from the world of DC Comics. As Green Arrow, “I try to help others, save the city,” Ray says. “Fighting crime, beating up bad people.”

At the sold-out fashion show, called “Beyond Trend,” a crowd gathered around a runway festooned in paper flowers. Artists strutted down the catwalk, modeling handmade Frankenstein masks, shrinky-dink jewelry, pom-pom-covered shawls, and sparkly tinsel headdresses. When Ray emerged as Green Arrow, cheers erupted and he struck a fierce pose, drawing back his bow and aiming the arrow into the crowd.

“He looked so confident that nearly everyone in the audience instinctively flinched, if not full-out ducked,” says Creative Growth staffer Jessica Daniel. “Of course, he didn’t shoot the arrow— it wasn’t a real arrow, anyway—but he was pretty proud of the reaction.”

Superheroes influence Ray’s real-world behavior, not just his art. He often rescues stray dogs he finds in his neighborhood. While skateboarding, he found an American bulldog on the side of the road, “looking really dehydrated.” He brought her home, named her Scuttles, and fed her plenty: “Now she’s fat.” Scuttles has two adopted siblings: a rescued Newfoundland named Ace and a bearded dragon named Hero.

“Ray is one of the most caring, sensitive, empathetic people I know,” Matt says. Superhero persona aside, “he couldn’t just see a dog looking hungry on the street and leave it there.”

But Ray doesn’t consider his empathy a superpower. “I don’t have any powers in my world,” he claims. Given the choice to have any superpower, “I would probably pick super-strength, so I could pick up literally anything,” he says, spinning his fidget-spinner. “If I was walking down the street one night and saw someone trying to kidnap somebody, I could just stop their car with my hand and rip their tire off. I can see it now.” He cocks his head to the side and gazes into the distance.

“When I daydream,” he explains, “I tip my head a little to the left.”

This is part two of four of Folks’ series of profiles of some of the amazing artists at Oakland’s Creative Growth Arts Center, which serves artists with developmental, mental and physical disabilities.

For original article, visit folks.pillpack.org.

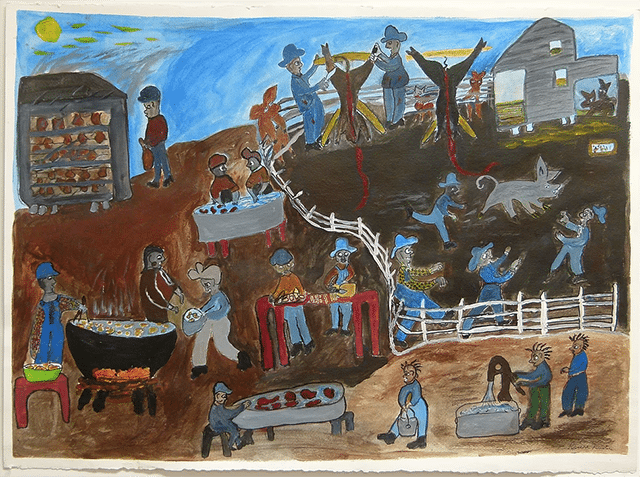

Rickie Algarva Featured | Folks Magazine | June 2017

The “Good Witch” Artist Finds Her Niche Fun-loving psychedelic explorer Rickie Algarva was never able to hold down a job due to her learning disabilities. Now 76, her artworks sell for up to $750 apiece.

By Carey Dunne June 16, 2017

Hamburgers grow on trees, a man on a hoverboard flies over a waterfall, Ra the Sun God stares down a monkey riding a horse: If you saw Ricketta “Rickie” Algarva strolling down the street with her walker one day, you probably wouldn’t guess that these sorts of wild images churn beneath her orange bucket hat. At 76, with cropped white hair and hearing aids, the petite, soft-spoken artist creates psychedelic worlds as dazzling as Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland.

For the past twenty-nine years, Rickie has worked out of Creative Growth Art Center, a nonprofit organization that serves artists with developmental and physical disabilities in Oakland, California. Founded in 1974 by an art educator and a psychologist in their Berkeley garage, Creative Growth now provides more than 150 artists with supplies, gallery representation, and professional studio space in a cavernous former auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland.

“Shall I add some birds here?” Rickie muses one morning in the studio, painting technicolor accents onto her latest wooden sculpture. It features a few of her trademark motifs: Waterfalls, wine bottles, flying people, flying hamburgers. (Rickie emphasizes that her interest in hamburgers is purely aesthetic: “I don’t eat hamburgers. Only once in awhile. They’re greasy. All that fat in ‘em.”)

Born premature at East Oakland Hospital in 1941, infant Rickie weighed just three pounds, eleven ounces. “I wasn’t expected to live,” she says, let alone to become a professional artist. While growing up in Oakland, decades before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, she didn’t receive much support for the learning disabilities that resulted from her premature birth. As a student at Fremont High School, she was constantly made to feel “slow.”

“Back then, it was different,” she says. “It was hard for me to learn.” To escape, as a kid, “I was always playing with polliwogs in the creek. I was a tomboy.” She also drew pictures: “I always wanted to be an artist.” But nobody encouraged her pursuit of art. Rickie’s father, a first-generation Italian immigrant who worked at the Port of Oakland, “was very high-strung, and had a temper,” she says. “My mother was the sweetest person, but my father would get real mad if he tried to show me a problem and I couldn’t do it. It wasn’t a good environment.”

She holds no resentment, though: “You can’t change the past,” she says, channeling the wise monkish figures she often draws, who levitate with eyes closed on magic carpets. “It’s already gone.”

In Rickie’s generation, people with disabilities usually had two dismal options: either to be institutionlized.. or to ‘go with the flow’.

In Rickie’s generation, people with disabilities usually had two dismal options: “Either to be institutionalized or pushed to the edges of society, or to ‘go with the flow’ and fake their integration into ‘regular’ or ‘normative’ society,” Creative Growth Studio Manager Matt Dostal says. Rickie was able to do the latter—she attended mainstream public schools, married, had a daughter, then got a divorce—but it wasn’t until she joined Creative Growth in her forties that she found the artistic and educational resources she craved growing up. Since then, she’s created an astonishing body of Surrealist work: Hand-bound books, colorful rugs, painted wooden dioramas.

“Creative Growth kickstarted my art career,” Rickie says. “There’s no words to tell you how happy I am being here. My art makes me happy, and it makes other people happy, too. Especially when you sell it. [Creative Growth] gave me a job. I never had a job outside the home. My learning disability made it difficult to find employment.” Now, her rugs sell for up to $750 apiece. Her vivid colors and strange creatures are a hit in the San Francisco Bay Area, the epicenter of the sixties’ hippie modernist art movement.

“I never had a job outside the home. My learning disability made it difficult to find employment.” Now, [Rickie’s] rugs sell for up to $750 apiece.

“Rickie has such an unassuming physical presence, but she’s a fun-loving psychedelic explorer,” Dostal says. “For Christmas one year, Rickie asked her sister for a Cream album—because she thought it would help her with her artwork.” But unlike the British rock supergroup, Rickie seeks no chemical assistance for her visions. Her artistic inspirations range from Egyptian mythology to a guy she saw hoverboarding on the sidewalk to her favorite TV show, Ancient Aliens, on the History Channel.

Usually, Rickie is as amused and mystified by the products of her imagination as anyone. “Where the heck do you come up with this stuff?” asks Kathleen Henderson, a Creative Growth staffer. Rickie shrugs: “It’s almost like a freestyle. It all just comes out of my head.”

In May, after celebrating her 76th birthday and watching her 47-year-old daughter graduate from Merritt College with a degree in Genetic Counseling, Rickie started working on illustrations for a new children’s book. Instead of adding words, she’s leaving blank lines beneath each illustration, so that children can interpret the pictures themselves and write their own stories.

When I ask how the characters in one drawing plant their hamburger trees, Rickie deadpans: “These kids just throw hamburgers in the ground and they grow,” she explains. “If they wanted to grow a sesame seed bun, all they’d have to do is put sesame seeds in the ground.” She starts laughing hysterically, tears streaming down her cheeks. “Oh my goodness,” she says. “Oh my goodness.”

She points to a character wearing harem pants and a bowtie. “He’s a fantasy guru,” she says. “He’s gonna change these snakes into tree branches by casting a spell over them.”

I ask Rickie if she ever casts similar spells. “No,” she says, with a sly smile. “I’m a good witch.”

She colors quietly for a bit, then pauses: “You know, I was lying in bed the other night, thinking about what my next drawing is gonna be, and I was thinking it would be some kids riding a tricycle. But instead of wheels on the tricycle, do you know what I was thinking there would be?” She raises her eyebrows.

“I think I might know,” I say, and she nods.

“Hamburgers,” she says, and grins, then resumes coloring her fantasy guru’s harem pants pink.

This is part one of four of Folks’ series of profiles of some of the amazing artists at Oakland’s Creative Growth Arts Center, which serves artists with developmental, mental and physical disabilities.

For original article, visit folks.pillpack.com.

Creative Growth Featured | Amtrak's The National | June/July 2017

Next stop: Oakland

Where Creative Growth, a center for artists with disabilities, is shepherding America’s next Andy Warhol

Story by Joshua David Stein Photography by Carlos Chavarría June/July 2017 Issue

L-I-G-H-T Space L-I-G-H-T Space L-I-G-H-T

The two-part click-clack of an old Brother word processor keyboard keeps time on the second floor of a converted auto body repair shop in Downtown Oakland, California. Since 1982, the large brick industrial space has housed Creative Growth Art Center, a gallery and busy workshop for artists with developmental disabilities. At the typewriter sits Dan Miller, one of the 160 artists who work with the organization.

Like many of the artists here, Miller, 56, has autism. Today, he’s using a ream of paper that extends scroll-like out of his typewriter—“Dan Miller’s typewriter,” per the message Sharpied across the carriage—but he often draws or paints the words, over and over again, over and over one another, until their limbs form thick abstract clouds and their meaning becomes lost in a cartoon tussle of lines.

Miller is in one of the two smaller studios located on the second floor of Creative Growth. On the open floor below, tables covered in brown butcher paper—around which artists sit deeply and solitarily engaged in their work—are laden with a buffet of crayons, markers, pencils, and other art-making materials. At one table, Monica Valentine sits before a large Styrofoam cube and a tray of brightly colored beads, sewing pins and sequins. The funny and chatty 62-year-old has autism, and is wearing a green bicycle reflector as a necklace. She is also blind and claims she can sense the colors of her art materials by touch: blue is cold, yellow is warm, green is cool. She is in the process of covering the entire Styrofoam cube in a dense coat of beads and sequins, held together by pins, until the sculpture looks like a glorious geometric Technicolor porcupine. Meanwhile, Jane Kassner sits at another table, her walker beside her. A minimally verbal 62-year-old with Down’s Syndrome, she is working, as usual, on advertisements cut out of old Artforum magazines. She grabs a brush and paints over the slick ads for gallery shows in New York, London, and Tokyo. Beneath a swirl of brilliant orange paint disappears Andy Warhol’s Brillo box. With one stroke of blue paint, most of renowned artist Barbara Kruger’s words are obliterated. The only words showing are Look and listen.

It’s tempting to read Kassner’s work as a biting critique of commodification in the art world, but the artist and her colleagues here at Creative Growth pay no heed to auctions, collectors, patrons, and galleries. Their indifference, however, is unrequited. In fact, a growing number of Kassner’s colleagues are increasingly being embraced by the very same art establishment that has fallen underneath Kassner’s brush. Two years ago, Creative Growth’s John Martin, a 54-year-old artist who has been with the organization for 30 years, sold 35 colorful cutout sculptures to Facebook. Martin’s work now hangs alongside established contemporary artists like Drew Bennett and David Choe in the tech giant’s massive new headquarters in Menlo Park, California. With other Creative Growth artists fetching top dollar from established collectors, this Oakland nonprofit rivals some of the country’s most reputable M.F.A. programs as an incubator and feeder for the global art market. In Creative Growth’s biggest coup yet, Dan Miller, the artist currently sitting at the Brother word processor, and the late Judith Scott are included in this year’s Venice Biennale, by far the most prestigious art show in the world.

“This really represents a huge advancement in how people appreciate and value the work of artists with disabilities,” says Tom Di Maria, the center’s high-energy director since 1999, who’s presently giving me a tour of the facilities. Di Maria tells me that he bristles when asked, often in hushed tones at art fairs, what’s “wrong” with his artists. “People push for it, but l say, ‘I don’t know. What’s wrong with you?’ We ended up in the Biennale because we haven’t led with disability or charity. We’ve led with high-quality art.”

The Central Pavilion at the 57th edition of the Venice Biennale is a world away from the Oakland garage where, in 1974, artist and educator Florence Ludins-Katz and her husband, psychologist Elias Katz, started Creative Growth with just a few tables and cans of paint. “It’s the classic entrepreneurial Bay Area story,” says Di Maria. “Think of all the companies founded in a garage that have gone on to affect culture.”

At the time, the couple was less interested in affecting culture than having an impact on the lives of the thousands of developmentally disabled Californians released from state institutions by the 1972 implementation of the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act. Although it was an outgrowth of the Independent Living Movement that sought to give the disabled equal rights, the LPSA effectively abandoned the disabled to poorly run and poorly funded county programs. Many experts agree that the act began what is known as the “institutional circuit,” whereby the disabled cycle through hospitalization, incarceration, and homelessness in endless revolutions of misery.

Elias Katz saw this unfold firsthand at the Sonoma State Home, where he worked. And since Florence Ludins-Katz taught art at both the high school and college levels, Creative Growth was the couple’s natural response. But it was more than just the Katzes that led to Creative Growth. Due credit must be given to the specific place and time of the art center’s founding: Oakland, 1974. To the immediate north was Berkeley and across the Bay was Haight-Ashbury, the political and creative centers, respectively, of the previous decade’s counterculture. As Lori Fogarty, the director of the Oakland Museum of Art, notes, “In Oakland in particular, there’s a long history of social justice work blending with artistic activity.”

By 1982, the Katzes had outgrown the garage and purchased the old auto body shop on what was then called Broadway’s Auto Row. It has been the organization’s home ever since. Just as the East Bay shaped Creative Growth, Creative Growth began to shape this little corner of the East Bay. Once a bustling commercial corridor full of car dealerships and auto repair shops, by the 1970s Oakland’s Auto Row was largely barren. This decline was partially a result of the white flight of the 1960s as well as to the interstate system, which not only served as the escape route to the suburbs but also lopped off Auto Row from the rest of Oakland. By the time Creative Growth moved in, the area was sufficiently fallow that a nonprofit with hardly any funding could buy a building. Even in 1999, when Di Maria joined, he remembers, “You had to jump in your car to go get a cup of coffee. There was nothing here.”

Di Maria bristles when asked what’s “wrong” with his artists. “I say, ‘I don’t know, what’s wrong with you?’”

Today, the blocks around Creative Growth are beehives of construction. In 2007, California Governor Jerry Brown, who was then the mayor of Oakland, introduced an initiative called the 10K Project to develop the neighborhood. According to Brown, if he could lure 10,000 people to settle in Downtown Oakland, the city would flourish. Ten years later, buildings continue to be constructed. There’s coffee now too. Around the corner from Creative Growth, at an art gallery and espresso bar called Tertulia, young professionals drink Stumptown coffee, savor artisanal doughnuts, and make use of the Wi-Fi. There are scores of other galleries in the neighborhood, like Transmission and Aggregate Space, and restaurants like Agave Uptown and new trendy eatery LocoL. Creative Growth, meanwhile, continues to be involved in the artistic ferment, as one of the founders of Art Murmur, a gallery crawl that draws nearly 10,000 people on the first Friday of every month. “It’s amazing to think that when Creative Growth first opened, there were no galleries in Downtown Oakland,” says Di Maria. “Art Murmur just shows how far we’ve come.”

But much as it has been in gentrified neighborhoods from Silver Lake in Los Angeles to Williamsburg in Brooklyn, “discovery” often means displacement—for both the marginalized communities that were historically there and the artists who helped spur the growth. “There are lots of people who are artists working two or three part-time jobs so they can pay this egregious rent,” says Ari Takata-Vasquez, owner of a small boutique in Oakland called Viscera, about the impact that tech money has had on the Oakland real estate market—which according to online database Zillow includes the five hottest neighborhoods in San Francisco’s metropolitan area. At Creative Growth, which employs 18 professional artists to help assist its members in technical matters, the shifts are felt.

“We’re okay because we own the building,” says Di Maria. “But many of our professional artists can’t afford to live in Oakland anymore. Many are faced with dislocation.” At this, Di Maria nods to Steve Oriolo, a studio instructor who works with Miller twice a week. Oriolo peers over Miller’s shoulder. “Does that say chandelier?” he asks. “Chandelier, right?” replies Miller, as he types the word for the hundredth time.

Meanwhile, Creative Growth’s mission is the same as it was in 1974: “To allow people with disabilities to grow and to be creative,” says Di Maria. “Importantly, the Katzes also hoped their people could eventually exhibit and sell their work to become professional artists.” With the inclusion of Miller’s work in the Biennale, says Di Maria, “Dan’s finally proving that artists with disabilities aren’t in the ghetto. They aren’t disenfranchised. They can be cultural leaders too.”

For original article, visit AmtrakTheNational.com.

Judith Scott Featured | NOW Toronto Magazine | October 2016

Judith Scott fit the textbook definition of an outsider artist: she had Down syndrome, was non-verbal and spent much of her life in an institution.

Made by people outside the mainstream art world – visionaries, eccentrics, psychiatric patients – outsider art's become a major force in the U.S., with its own galleries and museums, glossy magazine (Raw Vision) and art fair.

But Scott's startlingly contemporary sculptures are getting exhibited without qualification, making us question whether the outsider category still serves a purpose.

Says curator Matthew Hyland, who's brought the Scott show to Oakville Galleries, "It's been an ultimately unsatisfying and unsuccessful exercise to place the work of artists with disabilities into its own school or movement. It separates them from the general culture and suggests they live in a different world than we do.

"There's been a turn away from that, this exhibition being an example. Scott's work is significant not as a body of outsider art but as a body of contemporary sculpture."

Though many writers warn us not to read too much of Scott's biography into her art, her story is too inspiring to ignore.

Judith and twin sister Joyce were born in the U.S. Midwest. A childhood illness left Judith deaf, a condition that went undiagnosed for years. At seven, Judith was put in an institution, where she remained for 37 years, until Joyce got custody of her and brought her to California.

Joyce enrolled Judith in Oakland's Creative Growth Art Center, where at first she showed little interest in art. Then a textile workshop awakened her, and she spent most of the next 18 years, until her death in 2005, constructing her amazing wrapped sculptures in her own workspace at the studio.

Creative Growth first circulated Scott's work in an outsider context.

"But there was an understanding that it would ultimately transcend those categories. There was an inevitability to it," Hyland says. "For me, these are just some of the most remarkable sculptures that have been made in the last 70 years, full stop."

Last spring, Eliza Chandler, then artistic director of Tangled Art + Disability, which opened Tangled Art Gallery at 401 Richmond, told NOW that outsider shows often "send a message that the work is brilliant in spite of the artist's dislocation, madness, disability or isolation. It leaves us with the idea that disabled artists can't improve. Tangled works really hard to push back against that presumption."

On the other hand, Ellen Anderson, founder of Creative Spirit Art Centre, a 24-year-old Toronto studio and gallery inspired by Creative Growth, feels Canada lags behind the U.S. in promoting outsiders.

"They're a much more sophisticated art market. We're very naive and provincial in Canada. We've given Scott an exhibition, but we haven't given anyone here an exhibition."

She links the burgeoning U.S. outsider market to provisions about art in the Americans With Disabilities Act. "Access to the arts there is a right, not a privilege," she says.

Scott's story leads us to wonder if other artists with untapped potential are languishing, waiting for support and opportunity. The show also raises fundamental questions about what makes art speak to us - not verbal explanations or intellectual rigour, but its creator's passion for a unique visual language.

Judith Scott at Oakville Galleries, Centennial Square (120 Navy, Oakville), to December 30. 905-844-4402.

Creative Growth Featured | The Daily Californian | October 2016

Creative Growth Center: An unwavering community in an ever-changing Oakland By Rebecca Hurwitz October 23, 2016

The corner of 24th and Valdez in Uptown Oakland, where you’ll find the Creative Growth Art Center, is home to a lot of contradictions. Blocks of boarded-up businesses are punctuated by tall glass buildings, while kids in hand-me-downs sit at Lake Merritt picnics next to men in suits talking deliberately (and loudly) into their smartphones. Meanwhile, new boundaries and new obstacles related to subculture and accessibility spring up daily — but an unexpected subproduct of this change (at least in its current state) is a fusionist atmosphere where there is seemingly something for everyone in Oakland.

People often talk about the intersection of accessibility — in regards to subcultures, race and diversification — when discussing Oakland, yet accessibility for people with disabilities is an oft-neglected topic. There is one very special place in Oakland, however, creating a safe haven for people with disabilities. The Creative Growth Art Center provides free artistic space, materials and instruction for both adults and young adults with disabilities. It’s a professional gallery and art studio — think pottery wheels and drawing tables and a woodshop and miles of fabric and materials — housed in a warehouse, and all of the artists have some form of mental, physical or developmental disability.

To Julie Alvarado, studio manager, the center is much more than a place to make art — the pieces created there make a larger statement about ability and disability.

“The Creative Growth Art Center is not a place that produces and exhibits ‘disabled art,’ ” Alvarado said. “Instead it is simply art that is made by artists who have a disability.” In 1974, the husband and wife pair of Florence Ludins-Katz and Elias Katz (Ludins-Katz was an artist and Katz was a psychologist) started Creative Growth in their garage. “In a moment where funding was cut, a lot of people were deinstitutionalized and taken out of these environments where they were taken care of,” said Jessica Daniel, marketing and community development manager at center. “(They were) kind of set free, and there was a sense of need for people to have a place to go, a community where people can find their voices and express themselves.” This need was filled by Creative Growth. More than 150 artists are served at the studio, with about 90 working on pieces each day. Similar to the way California’s public schools work, Creative Growth gets a certain amount of money from the state per head, Daniel explained. This public funding coupled with the fact that Creative Growth owns its building allows the center to stay open in an ever-changing Oakland. In addition to the studio space, there’s a gallery component of the building where art is curated and displayed in a professional setting.

Daniel also spoke about the process by which the art made at Creative Growth achieves success in the mainstream art world.

“You know, everybody wants to show their art and share their life, and it’s pretty special.”

“We exhibit (the artists’) work in our gallery as well as at international art fairs, and we represent them the way a regular gallery would represent any artist: getting them into museum collections, into the right kind of collections in general,” she said. Former Creative Growth artist Judith Scott, who was deaf and had Down syndrome, has sculptures currently showcased in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Collection de l’Art Brut in Switzerland and the Museum of Everything in London, among other collections.

Daniel describes Creative Growth’s annual fundraiser, a fashion show, as “a really great big celebration of everybody here,” and even on an average Thursday morning, Creative Growth seems like a celebration. As a guest in its studio, I was genuinely welcomed with open arms, with many artists coming over to say “hello” and show me their work. Monica, one of the artists who welcomed me wearing a necklace crafted out of bike reflectors, asked me if I have a bike. She was looking to add to her collection. Min showed me her pottery based on Minions: “If you’re into minions, go here! Yeah that’s mine, that’s mine!” To Rydell, another artist, Daniel called out, “You’re looking good in the corduroy!” Rydell responded, “New, that’s my new pants,” and Daniel warmly replied, “Looking good, I like the ‘all gray’ look too.” She turned to me and commented, “Yes, there are a lot of personalities here. I really get to know a lot of the artists. … It’s fantastic, the best thing about being here.”

Artists at Creative Growth are not static; there is a lot of collaboration and community engagement involved in the creation of a piece. Seeing the artists diligently at work, perched at tables and motioning to one another, it’s clear the impact that art makes on these their lives. “You know, everybody wants to show their art and share their life, and it’s pretty special,” said Daniel. Daniel said that this presents a great opportunity for the greater community to get involved — even college students can become members for $25 per year, and membership gives access to studio tours and discounted artwork. There are many tiers of prices for CG artwork, and by buying a piece from Creative Growth, you don’t only get a beautiful piece of art, but you also get to support a program that means so much to so many people. The openness and accessibility of CG is quite rare for an art studio, and Daniel commented on it: “You’ll often get to see (a piece of art) hanging on a wall, but here you get to see it in action, see that there is a lot of artistic practice, and that does result in a lot of beautiful art. So it’s a pretty special thing.”

In a world where there seems to be fewer and fewer opportunities and spaces for disabled people, Creative Growth is here to stay. Amid the contradictions of Oakland — pop-up beer gardens next to decrepit pawn shops, one of the lowest-ranked school systems in America neighboring a store that sells belts that will set you back $200 — there lies a much happier contradiction. That of a professional, sophisticated art studio using its resources not to cater to the pretentious, wealthy crowd, but instead showcasing the art of people whose voices might not be able to be found and heard otherwise.

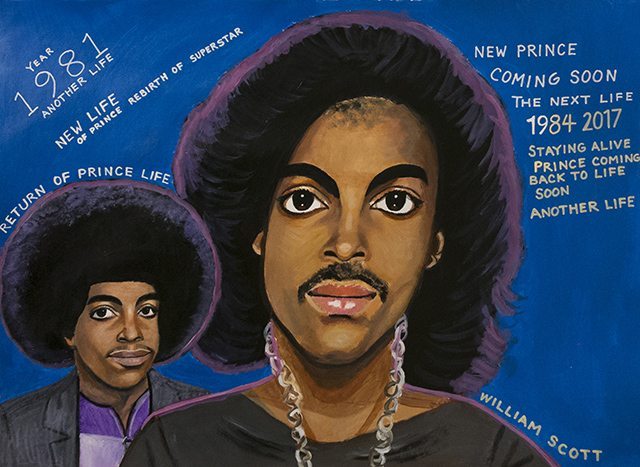

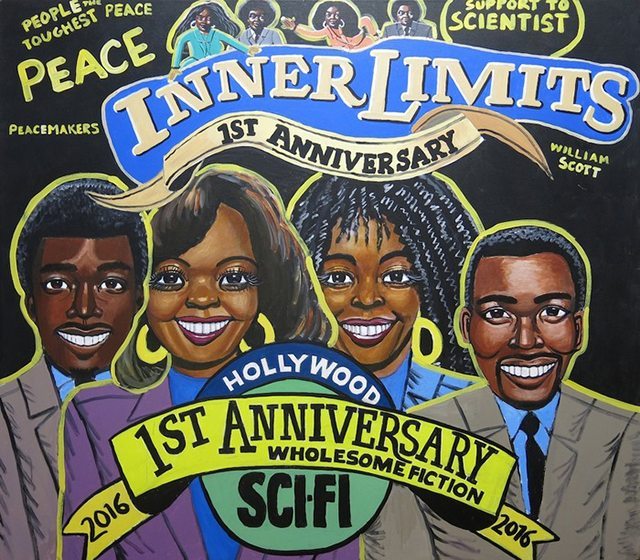

William Scott Featured | VICE | October 2016

Prince Inspires a Sexy Purple Art Show The Purple One gets the royal treatment at Minnesota Street Project’s Prince-themed exhibition.

By DJ Pangburn October 3, 2016

When iconic musician and pop star Prince passed away in April, the tributes rolled in. Around this time, writer, critic and curator Glen Helfand decided he wanted to organize his own tribute for the Purple One. The result is After Pop Life, an exhibition of Prince-inspired art now on at Minnesota Street Projectin San Francisco.

Helfand tells The Creators Project that After Pop Life is a follow-up to an exhibition he organized back in 1993. At the time, Helfand was a Prince fanatic and making his way in the art world. Wanting to explore how Prince created a musical and visual universe, he enlisted friends to make art in honor of Prince. Though he drifted away from Prince’s more recent records, Helfand was again inspired by the late artist’s Oakland show in March of this year. And when Prince passed away, Helfand was struck by the outpouring of grief, so he posted an announcement to the first show, then felt encouraged enough by the responses to update the project.

In Rex Ray’s “cross piece,” the artist forms a religious icon of related hand gestures taken from album covers by Prince, David Bowie, and Roxy Music. In The Artist, Luke Butler creates a paper doll piece that Helfand says “speaks to the idea of how we manipulate our idols, we can literally play with his sexiness, transcendence, and flash.”

“The video by XUXA SANTAMARIA, a musical collaboration by Sofia Cordova and Matt Kirkland, captures that feeling of being alone in your childhood bedroom bonding with a song—it gives me goosebumps,” says Helfand. “Maria Guzman Capron’s sculpture does something similar... Tamra Seal describes her glowing orb piece as a drop of purple rain on a patch of like-colored astroturf; it’s a portal to another dimension.”

Elsewhere, Jason Lazarus shows a text-based piece that recounts how Prince got the Super Bowl Halftime Show. According to Helfand, Prince likened to the situation to what it’s like for an artist to have a studio visit. In another piece, artist Didi Dunphy crafts a cushioned purple skateboard that would have been fit for Prince’s plush persona and lifestyle.

“I am happy to have included works by artists working in studios for developmentally disabled artists as there is often deep identification with famous figures in that work,” Helfand notes. “William Scott, an artist who works with Creative Growth in Oakland, is noted for his works honoring soul music, and with that painting he anticipates Prince’s rebirth. Yukari Sakura, who works with Creativity Explored in San Francisco, makes paintings of desserts in honor of deceased celebrities, and here she offers a pie and a cake.”

Helfand also worked with a young collective called Bonzanza, who work in various media, including fashion. Currently they are at work on a show for the closing party. Titled 23 Positions in a One Night Stand, Bonanza are planning to invoke 23 Prince looks, including the yellow buttless pants that Prince wore on the MTV Music Awards while performing “Gett Off.” “It’s going to be glittering and sexy,” Helfand says.

Ideally, Helfand hopes that with After Pop Life people can ponder and appreciate Prince as a meaningful artist, not just a pop star. He also hopes that visitors are able to think about how people “claim” certain artists.

“The most obvious way this happens is through karaoke, and Jenifer Wofford’s Dearly Beloved Karaoke Chapel is literally a place of worship that is giving people a site to both grieve and feel joy,” he says. “Jenifer was one of the key people who encouraged me to mount this show. But other artists in the show, Rodney McMillian, XUXA SANTAMARIA, and Laura Hyunjhee Kim each made videos in which they somehow ‘own’ a Prince song.”

“With 38 artists in the show, I also wanted people to experience a sense of abundance, of the pleasure of seeing a lot of colorful (purple), sexy artwork to offer some solace for the passing of a great artist and some respite during this tense political moment.”

After Pop Life runs at Minnesota Street Project until October 1st. Click here for information on the closing party.

Click here to check out more of Glen Helfand’s curatorial work.

Tom di Maria Discusses Creative Growth's History on East Bay Yesterday Podcast | October 2016

Ronald Reagan inadvertently sparked the birth of one of Oakland's most renowned and visionary art organizations. Find out how in this episode of East Bay Yesterday that explores the explosion of "outsider" art, the redevelopment of Uptown and the gentrification crisis. Featuring Tom di Maria, director of Creative Growth. Listen here!

Judith Scott Featured | Huffington Post | September 2016

The Beautiful Story Of An Artist With Down Syndrome Who Never Spoke A Word: Judith Scott’s twin sister Joyce tells her story. by Priscilla Frank September 6, 2016

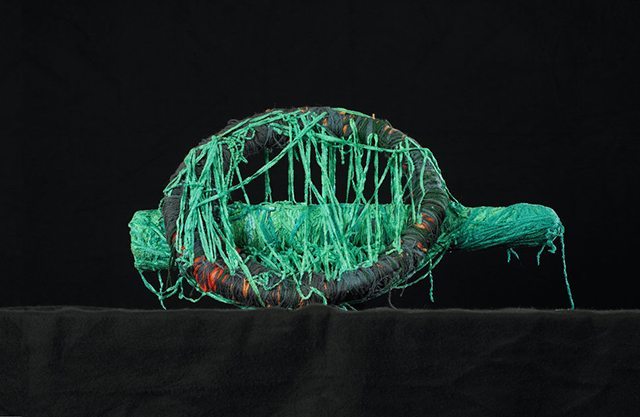

Judith Scott’s sculptures look like oversized cocoons or nests. They begin with regular objects ― a chair, a wire hanger, an umbrella, or even a shopping cart ― which are swallowed up whole by thread, yarn, cloth and twine, swathed as frenetically as a spider mummifies its prey.

The resulting pieces are tightly wound bundles of texture, color and shape ― abstract and yet so intensely corporeal in their presence and power. They suggest an alternate way of seeing the world, not based on knowing but on touching, taking, loving, nurturing and eating whole. Like a wildly wrapped package, the sculptures seem to possess some secret or meaning that can’t be accessed, save for an energy that radiates outward; the mysterious comfort of knowing that something is truly unknowable.

Judith and Joyce Scott were born on May 1, 1943, in Columbus, Ohio. They were fraternal twins. Judith, however, carried the extra chromosome of Down Syndrome and couldn’t communicate verbally. Only later, when Judith was in her 30s, was she properly diagnosed as deaf. “There are no words, but we need none,” Joyce wrote in her memoir Entwined, which tells the confounding story of her and Judith’s life together. “What we love is the comfort of sitting with our bodies near enough to touch.”

As a kid, Joyce and Judith were wrapped up in their own secret world, full of backyard adventures and made-up rituals whose rules were never said out loud. In an interview with The Huffington Post, Joyce explained that during her youth, she wasn’t aware that Judith had a mental disability, or even that she was, in some way, different.

“She was just Judy to me,” Joyce said. “I didn’t think of her as different at all. As we got older, I started realizing that people in the neighborhood treated her differently. That was my first thought, that people treated her badly.”

When she was 7 years old, Joyce awoke one morning to find Judy gone. Her parents had sent Judy to a state institution, convinced she had no prospects for ever living a conventional, independent life. Undiagnosed as deaf, Judy was assumed to be far more developmentally disabled than she was ― “uneducable.” So she was removed from her home in the middle of the night, rarely to be seen or spoken of by her family again. “It was a different time,” Joyce said with a sigh.

When Joyce went with her parents to visit her sister, she was horrified at the conditions she encountered at the state institution. “I’d find rooms full of children,” she wrote, “children with no shoes, sometimes with no clothes. Some of them are on chairs and benches, but mostly they are lying on mats on the floor, some with their eyes rolling, their bodies twisted and twitching.”

In Entwined, Joyce chronicles in vivid detail her memories entering adolescence without Judith. “I worry that Judy might be forgotten completely if I don’t remember her,” she writes. “Loving Judy and missing Judy feel almost like the same thing.” Through her writing, Joyce ensures that her sister’s painful and remarkable story will not be forgotten, ever.

Joyce recounts the details of her early life with startling accuracy, the kind that makes you question your ability to render your own life story with any sort of coherence or verisimilitude. “I just have a really good memory,” she explained over the phone. “Because Judy and I lived in such an intense physical, sensate world, things were kind of burned into my being much more strongly than if I spent a lot of time with other kids.”

As young adults, the Scott sisters continued living their separate lives. Their father passed away. Joyce got pregnant while in college and gave the child up for adoption. Eventually, while speaking on the phone with Judy’s social worker, Joyce learned that her sister was deaf.

“Judy living in a world without sound,” Joyce wrote. “And now I understand: our connection, how important it was, how together we felt each piece of our world, how she tasted her world and seemed to breathe in its colors and shapes, how we carefully observed and delicately touched everything as we felt our way through each day.”

Not long after that realization, Joyce and Judy were reunited, permanently, when Joyce became Judy’s legal guardian in 1986. Now married and a mother of two, Joyce brought Judith into her Berkeley, California, home. Although Judith had never displayed much interest in art before, Joyce decided to enroll her in a program called Creative Growth in Oakland, a space for adult artists with developmental disabilities.

From the minute Joyce entered the space, she could sense its singular energy, founded upon the urge to create without expectation, hesitation or ego. “Everything radiates its own beauty and an aliveness that seeks no approval, only celebrates itself,” she wrote. Judith tried out various media introduced to her by the staff ― drawing, painting, clay and wood sculpture ― but expressed interest in none.

One day in 1987, however, fiber artist Sylvia Seventy taught a lecture at Creative Growth, and Judith began to weave. She started by scavenging random, everyday objects, anything she could get her hands on. “She once grabbed someone’s wedding ring, and my ex-husband’s paycheck, things like that,” Joyce said. The studio would let her use nearly anything she could grab ― the wedding ring, however, went back to its owner. And then Judith would weave layer upon layer of strings and threads and paper towels if nothing else was available, all around the core object, allowing various patterns to emerge and dissipate.

“The first piece of Judy’s work I see is a twinlike form tied with tender care,” Joyce writes. “I immediately understand that she knows us as twins, together, two bodies joined as one. And I weep.” From then on, Judith’s appetite for art-making was insatiable. She worked for eight hours a day, engulfing broomsticks, beads, and broken furniture in webs of colored string. In lieu of words, Judith expressed herself through her radiant hulks of stuff and string, bizarre musical instruments whose sound couldn’t be heard. Along with her visual language, Judith spoke through dramatic gestures, colorful scarves, and pantomimed kisses, which she would generously bestow on her completed sculptures as if they were her children.

Before long, Judith became recognized at Creative Growth and far beyond for her visionary talent and addictive personality. Her work has since been shown in museums and galleries around the world, including the Brooklyn Museum, Museum of Modern Art, the American Folk Art Museum and the American Visionary Art Museum.

In 2005, Judith passed away at 61 years old, quite suddenly. On a weekend trip with Joyce, while lying in bed alongside her sister, she simply stopped breathing. She had lived 49 years beyond her life expectancy, and spent nearly all of the final 18 making art, surrounded by loved ones, supporters and adoring fans. Before her final trip, Judith had just finished what would be her last sculpture, which, strangely, was all black. “It was so unusual she would create a piece with no color,” Joyce said. “Most of us who knew her thought it as a letting go of her life. I think she related to colors in the way all of us do. But who knows? We could not ask.”

This question is interwoven throughout Joyce’s book, repeated again and again in distinct yet familiar forms. Who was Judith Scott? Without words, can we ever know? How can a person who faced unknowable pain alone and in silence, respond only, unimaginably, with generosity, creativity and love? “Judy is a secret and who I am is a secret, even to myself,” Joyce writes.

Scott’s sculptures, themselves, are secrets, impenetrable heaps whose dazzling exteriors distract you from the reality that there’s something underneath. We will never know the thoughts that ran through Judith’s mind while she spent 23 years alone in state institutions, or the feelings that pulsed through her heart as she picked up a spool of yarn for the first time. But we can see her gestures, her facial expressions, the way her arms would fly through the air to properly nestle a chair in its fair share of tattered cloth. And perhaps that’s enough.

“Having Judy as a twin has been the most incredible gift of my life,” Joyce said. “The only time I felt a kind of absolute happiness and a sense of peace was in her presence.”

Joyce currently works as an advocate for people with disabilities, and is engaged in establishing a studio and workshop for artists with disabilities in the mountains of Bali, in Judith’s honor. “My strongest hope would be that there are places like Creative Growth everywhere and people who have been marginalized and excluded would be given the opportunity to find their voice,” she said.

Creative Growth Featured | VICE | August 2016

Meet the Disabled Artists Creating a New Space for Talent in the Art World

Meet the Disabled Artists Creating a New Space for Talent in the Art World

At the Creative Growth Art Center, a professional studio for artists with physical and intellectual disabilities, men and women gather in a shared workspace filled with paint, ceramics, and endless opportunities for creativity and joy.

By Jonathan Parks-Ramage August 17, 2016

Wall Street, 1987. A group of executives convenes in a mile-high boardroom. The atmosphere is tense, filled with the conflicting ambitions of ruthless stockbrokers.

"Buy low, sell high," their CEO decrees.

Suddenly, a woman dressed as the Kool-Aid Man interrupts the proceedings.

"Who wants to buy some Kool-Aid?" she yells.

The room erupts into cheers. Businessmen sip Kool-Aid from champagne flutes as Whitney Houston's "I Wanna Dance With Somebody" blasts over the speakers. The Kool-Aid Woman lip-syncs to the song as the meeting descends into chaos.

This is not, of course, a scene from actual Wall Street history. It is taken from a surreal video short, titled Three Moments in the Life of the Kool-Aid Guy, by rising contemporary artist Susan Janow. Though Janow's CV reads like those of other emerging stars in today's marketplace—with major exhibitions in Paris, New York, and Berlin—her personal biography is markedly different than those of her peers. She did not study at Yale, the Rhode Island School of Design, or any of the country's top fine arts programs. Janow is developmentally disabled. She has spent the entirety of her professional career working at the Creative Growth Art Center, a professional studio for artists with physical and mental disabilities.

Janow's video is one of the first pieces I see upon visiting Creative Growth's headquarters in Oakland, California. It is on display in the center's gallery, which exhibits new media works from the center's artists. The gallery is connected to Creative Growth's studio space—a vast, open-plan workroom with lofted ceilings and large windows.

"Creative Growth is an amazing creative community of artists, volunteers, clients, staff... we're all pretty much equal here. That's a really unique environment when you look at other programs for people with disabilities. They have a voice here," says Becki Couch-Alvarado, the center's executive director, as we tour the studio. "I don't think there are many opportunities in their lives for them to have that voice, where they're the focus of attention in a positive way."

Approximately 90 artists are assembled here, divided into groups and sitting at huge, white worktables. Creative Growth is equipped with resources to work on projects in any medium: painting, drawing, ceramics, embroidery, woodwork, and video. Staff members assist the artists, providing them with materials or facilitating the use of a kiln or table saw. The philosophy of Creative Growth is that these artists are inherently gifted—and only need space and support to realize their visions.

"I think everybody has a creative impulse, right?" Couch-Alvarado says, motioning to the workroom. "If you give someone the opportunity to use that impulse, they will. That's what we're doing here... and everybody has something to say."

Creative Growth nurtures bold new voices, and the art world is listening with increased interest. In recent years, Creative Growth has seen its artists enter permanent collections of museums like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Smithsonian, and the American Folk Art Museum. The center's clients have exhibited in art fairs and galleries worldwide, entered into collaborations with major brands such as Marc Jacobs and Barneys New York, and are privately collected by celebrities including Lady Gaga and Michael Stipe.

I sit down with Janow during her lunch break, curious to meet the artist behind the Kool-Aid video. Janow brought her preferred meal today: a hot dog (no bun or condiments), two packets of red Jell-O, and fruit punch Kool-Aid. Janow, who is 36, commuted to Creative Growth today from her home in San Leandro, where she lives with her stepmother. This is a common reality for many of Creative Growth's artists: some are capable of living on their own, but others with more severe disabilities reside in supported living centers or with relatives. Janow sports glasses and a near-permanent smile. She is gregarious and outgoing, speaking in loud staccato bursts, punctuated by laughter.

Janow explains that the idea for the Kool-Aid video started because she simply loves Kool-Aid. "I'm a Kool-Aid drinker. I just came up with the thing. I said, 'I drink Kool-Aid, so... why the heck not do a Kool-Aid commercial?'" she says, attacking her hot dog with a plastic fork. Janow, a kinetic ball of energy, adds that she also loves Whitney Houston.

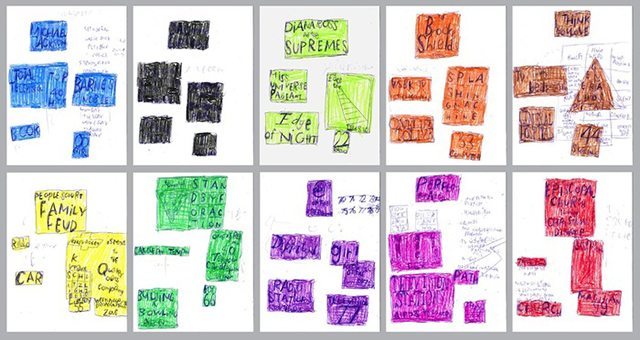

Apart from videos, Janow works with paint, wood, and ceramics, but drawing is her favorite medium.

Janow is also best known for her drawings: intricate geometric grids, rendered by hand in a stunning range of color. They have been exhibited at major art fairs—including Frieze, DDessin Paris Contemporary Drawing Fair, the Outsider Art Fair (in Paris and New York)—and will soon be featured in a large-scale installation in Anthropologie's Palo Alto store. Janow is successful enough to break out on her own but has no desire to leave Creative Growth; it is essential to her creative process and identity.

"I still come here because I love this place. I will not quit this place because I love it so much. This place is like home away from home number two. Once I got here, I was like, 'These are my people.' These are my people, and I'm sticking to it," Janow asserts.

This sentiment is shared by everyone I speak with at Creative Growth—both artists and staff. It was this unique environment that inspired Matt Dostal, now a ten-year employee, to first volunteer. "[When I first came here] I was completely moved by everything: the quality of art, the incredible artists—but also the sense of community," Dostal recalls. We speak in Creative Growth's woodworking area.

"We cultivate relationships that are part coworker, part friend, part family member. We spend more time with each other than most of our families. Many people with developmental disabilities are parked in front of the TV for the day, so this is an incredible social component for them," Dostal says.

"I found a calling I didn't know was out there."

Clearly, the program is a transformative experience for the artists, but it can be equally pivotal for the staff. "[Before Creative Growth] I studied art. But I was listless. I was working weird jobs," Dostal recalls. "This place grounded me... I found a calling I didn't know was out there. It's an incredible fusion of supporting an underserved and vulnerable population, coupled with intense creativity."

Dostal introduces me to John Hiltunen, another of Creative Growth's emerging stars. Hiltunen is 67, bald, and wears a plain T-shirt. Suspenders stretch across his stocky torso, holding up blue jeans. He sits at a table, working on a wood-mounted collage. He's manipulating a magazine cutout of a headless fashion model, gluing a dog face on her shoulders. The result is an absurdly chic Labrador puppy—sporting a sexy red jumper.

Hiltunen says he got the idea to do collage after a "special artist" visited Creative Growth a few years ago and the center's gallery displayed one of his collages. Dostal, observing our conversation, clarifies that it was noted collage artist Paul Butler.

Since then, Hiltunen has worked exclusively in collage. His work typically features comically composed animal/model mash-ups. These high-fashion non sequiturs have gained serious traction in the contemporary art market; Hiltunen's work has exhibited at prominent galleries like White Columns in New York and major contemporary art fairs such as Frieze and the New Art Dealers Alliance in Miami. Though his resume reads like that of a jet-setting art star, Hiltunen enjoys a much simpler lifestyle. Hiltunen first moved to the Bay Area from Texas to live at Serra Center, an independent and supported living center for adults with developmental disabilities.

"I've lived with [Serra Center] for the whole 39 years I've been [in the Bay Area]," Hiltunen explains. "First, they had a bunch of dormitories on a hill, and I lived there. But then I moved out, and... I've been living on my own for about 30 years. I'm still with the Serra Center. But I'm with the independent program."

Hiltuen lives with his wife, Carol, who also attends Creative Growth. They have been married for 29 years, and they met at Serra Center started coming to Creative Growth at the same time.

Hiltunen leads me to another table where he introduces me to his wife. She works on a sewing project as we chat about their relationship; she tells me that it's nice to be married to a fellow artist because it gives her more encouragement to do art.

Towards the end of our conversation, the room begins to stir as everyone migrates toward the lunchroom for today's big event: a meeting about the second issue of Creative Growth Magazine. Creative Growth artists are the magazine's sole contributors, and its publishing is a community effort. The first issue was carried in select galleries and bookstores in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The publication was the brainchild of volunteer/journalist Matt Haber and staff member Kathleen Henderson.

Haber and Henderson stand in front of the lunchroom as artists find seats for the meeting. The room buzzes with anticipation; the theme for the second magazine is about to be announced.

"We're here to discuss the next issue... and we have a theme: It's love!" Henderson announces.

There is a thunderous round of applause for love.

"Let's hear it for love!" Haber yells out.

"So, all kinds of love: brotherly love, sisterly love, carnal love, love of the vending machine," Henderson elaborates.

"What about love of animals?" asks an artist named Lisa, petting a raccoon stuffed animal.

"Yes, love of animals," Haber encourages.

"What else do we want to do in this magazine? What are some of your ideas?" Henderson asks.

The 90 or so artists begin shouting out topics for the love issue. Their ideas come rapid-fire as Haber takes notes: pets, couples, cruises, friendship, space, bed, fashion, teachers, horoscopes, Pokémon, God, and taco grease.

"I just want to say," Lisa pipes up, mid-brainstorm, "owning a dragon—I want an article about that in the magazine."

"About owning a dragon?" Henderson asks.

"Yeah, because when you own a dragon, you don't really know what you're getting yourself into," Lisa says, inspiring a wave of giggles.

"What about love of hot dogs?" Henderson asks. "I think there's someone at Creative Growth that really loves hot dogs..."

"That's gotta be me!" Janow shouts. The room breaks into knowing laughter.

"All right, we have a lot of good ideas. Who's excited for the next magazine?" Haber calls out. The room whoops and hollers.

The meeting adjourns. Everyone heads back to their workstations, chatting excitedly. The studio hums again with activity as artists dive into their projects.

I stay behind for a moment, perusing the previous issue of Creative Growth Magazine. In the back pages, I discover horoscopes written by the artists. The astrological predictions range from humorous ("Pisces: Be careful not to say anything racist at Fisherman's Wharf or you will have an accident.") to cryptic ("Libra: In 1 month, 3 Spanish models will come to America from Spain.") to blunt ("Virgo: You are never gonna change."). But it is the Aries forecast that resonates with me: "You will go on a trip to the happiest place on earth." Looking out at the workroom—brimming with creativity, joy, and life—it occurs to me that I already have.

William Scott Featured | ArtSlant | August 2016

Charting Experience: Four Artists with Developmental Disabilities Map Singular Visions By Sola Agustsson August 6, 2016

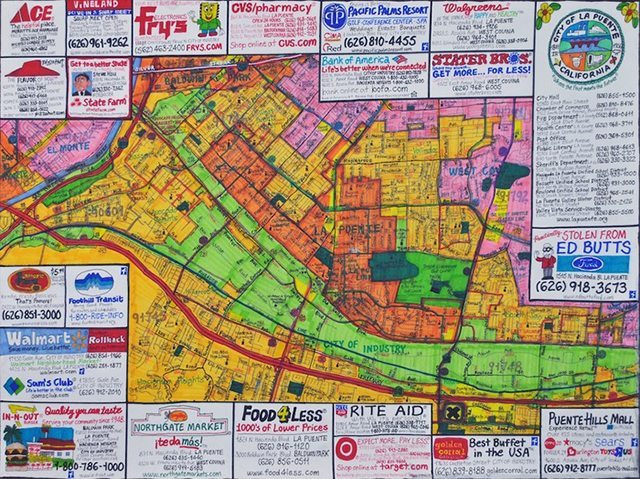

The process of creating art always involves transmitting one’s singular sensory experiences into a discrete vision. The Los Angeles exhibition Mapping Fictions brings together four contemporary artists who organize information and experience through text and images, charting popular culture, physical space, and personal knowledge in painstakingly detailed work. Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz of Disparate Minds curated the exhibition, which is now on view at The Good Luck Gallery, a space dedicated to self-taught artists. Disparate Minds is an organization that follows progressive art studios, described as “studio environments where adults with developmental disabilities can pursue and maintain lives/careers as artists.” Each of the artists in Mapping Fictions is neurologically or developmentally atypical, and works at a different progressive art studio.

Joe Zaldivar’s work reimagines screenshots from Southern California found on Google Street View. The snapshots are ephemeral, but his drawings of maps, buildings, and interiors reference specific local businesses. The titles and representations of these places are straightforward, pinpointing the moment in time quite factually. Yet, the drawings are subtly, humorously laced with cultural references. Bart and Homer Simpson, for example, turn up in The Coffee Roaster, 13567 Ventura Boulevard, Sherman Oaks, California, among other works.

Zaldivar’s YouTube channel has drawn over 2,000 followers, and lends insight into his particular vision. Recording directly from broadcast television, as well as VHS tapes he’s found at yard sales, Zaldivar pieces together seemingly isolated scenes. News segments, commercials, and movie clips from past and present blend together as white noise. But because he records them by hand, cam-style, the videos are a little shaky. It’s an idiosyncratic archive; inserting his presence into the documentation, Zaldivar hones in on recorded moments that are soon to be forgotten. His works highlight the markers of time, location, and pop culture as essential tools for processing information and charting our lives.

Daniel Green similarly turns his gaze on daytime television. His Days of Our Lives series structures personal events with the scheduling of popular soap operas. He intersperses the hourly schedules with illustrations of characters, logos, and personal commentary onto his mixed media on wood pieces, graphing them like TV Guides. The Sun (2010) reveals much about Green’s mapping of information by merging each December of the artist’s life with a television program from that time, reflecting on a universalized nostalgia for the cable television of our childhood. Now that we live in an era where television is as often streamed as it is broadcast at a set time, watching TV can be a less communally timed experience. But in the 1980s and 1990s, you had to be glued to a television to watch a show—and you could be sure thousands of other people were watching too.

Like Zaldivar, Green also combines pop culture iconography with the personal. In his portrait of the cast of Star Trek, for example, the artist infused facial features from his friends onto the television characters.

On the surface, many of these works and their organizational principles seem chaotic, yet there is a distinct order in the way each of the artists construct their works. Roger Swike draws his textual graphs intuitively at first, adding more deliberate details as he moves through the process. Later, he places them into color-categorized folders. Creating a lexicon of his own through numbers and pop culture references, he forms particular patterns in the pieces, which he later revisits to add further nuances to his own methods.

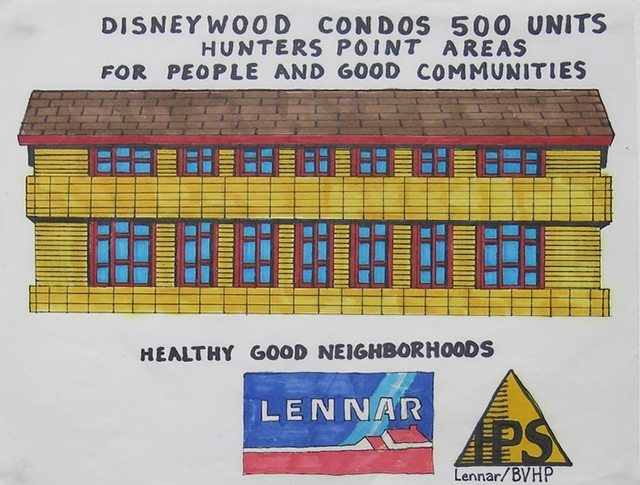

San-Francisco artist William Scott is interested in community-based organizing through activism and utopian philosophy. The exhibition includes some of the plans for Praise Frisco, the artist’s envisioning of a new city rising in the wake of a “cancelled” San Francisco, including a revitalization plan for his own socially marginalized area of Hunter’s Point. Ambitious and precise architectural drawings relay his idealist vision for the future.

All of the artists unlock ways of seeing the world through their work, specifically by incorporating text in their drawings and diagrams. Though we may not understand exactly how they view the world, through lists, architectural plans, maps, and pop culture symbols, we can concretely relate. List-making unifies in its inherent ability to convey how each person plans, schedules, and quantifies their existence—be it in the form of a daily routine or a list of goals. Pop cultural references bring together collective touchstones and experiences with the individual’s. And through maps and blueprints, a specific time and place can be mathematically pinned down. These methods of organizing and categorizing—list making, diagramming—give order and sense to all our lives. But the artists in Mapping Fictions show how these tools are not just personal, but communicative. They mediate their experiences of the past and dreams for the future in this public, yet intimate archive.

Sola Agustsson is a writer based in Los Angeles. She studied at UC Berkeley and has contributed to Bullett, Flaunt, The Huffington Post, Alternet, Artlog, Konch, and Whitewall Magazine.

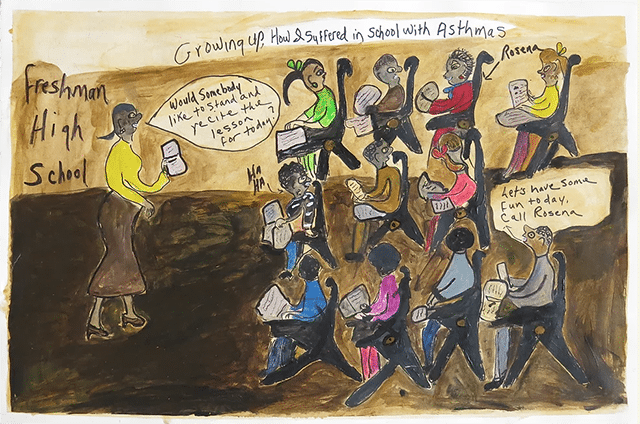

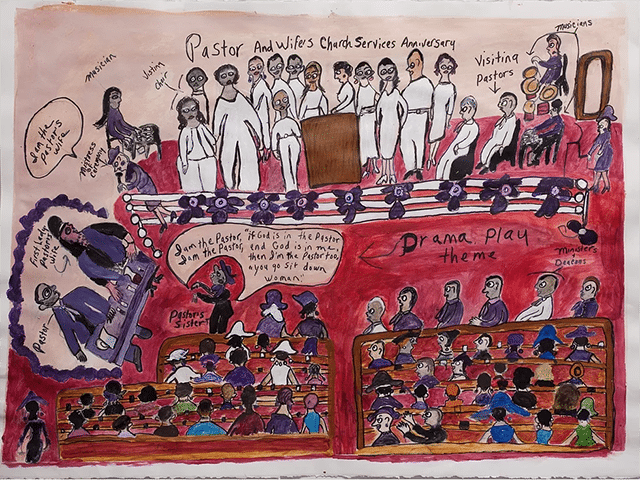

Rosena Finister Featured | Nat.Brut | August 2016

A Little Birdie Told Me

Work by Rosena Finister Essay by Danielle Wright August 2016